The EU spokesperson spoke recently about the low and falling rate of alignment of Georgia with the EU’s common foreign and security policy (CFSP). A closer look at the alignment pattern shows that the problem is not only quantitative but also qualitative.

Eka Akobia is an expert in International Relations, Dean and Professor at the Caucasus School of Governance

The countries aspiring to the EU candidacy and eventual membership must align their policies with the European Union. The rate of alignment is an integral part of the assessment of readiness for membership. Even as things currently stand, the Association Agreement between Georgia and the EU calls for “gradual convergence in the area of foreign and security policy.”

In its opinion on Georgia’s EU membership application from June 2022, EU Commission has stated that “efforts should be made to increase Georgia’s convergence with the Common Foreign and Security Policy, including on EU positions.” In the latest report published early in 2023, the Commission concluded that “Georgia is moderately prepared in this area. Additional efforts are needed to increase the convergence in the area of foreign and security policy, in particular, the alignment with EU statements and decisions as well as the application of restrictive measures when and where required.”

A deeper look

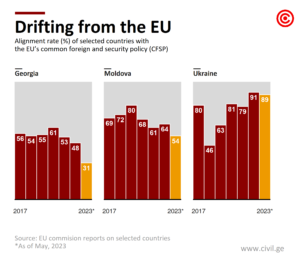

According to the web registry of the EU Council, in 2022 EU issued 107 declarations on EU decisions or statements in the area of CFSP, open for alignment by third countries. Out of 107 possibilities, Georgia aligned itself with only 51 declarations, registering a further drop from the previous year to 48%. Ukraine aligned itself with 97 EU declarations (91%), while Moldova aligned with 64 declarations (60%). The chart below, based on 2017-2021 Commission Opinions and the EU Council web registry for 2022, shows that Georgia’s convergence rate has been falling while those of Moldova and Ukraine – growing.

But the divergence goes deeper.

In 2022, the EU’s foreign policy actions covered 34 topics. Out of these, 23 items concerned specific countries, to which the EU devoted 92 declarations and invited third parties to align with it. In terms of its bilateral diplomacy Georgia had the lowest rate of convergence with the EU’s bilateral diplomacy outlook – it aligned with 31 declarations out of the 92 (34%), trailing far behind Ukraine (89%) and also Moldova (54%).

Out of sync on Russia

The EU made 26 declarations in 2022 that imposed sanctions on Russia for its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Georgia abstained from all but three of these declarations.

The three declarations it aligned with were related to “the non-government-controlled areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.” The reason for aligning with these three, in particular, seems to be Georgia keeping consistency with the opposition to legitimizing the non-recognized occupation/annexation regimes, which Tbilisi deems similar to those in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali region/South Ossetia.

Out of sync on thematic areas

In 2022, the EU covered 15 topical declarations ranging from human rights to chemical weapons. Out of these, Georgia aligned itself with ten (67%), compared with Moldova’s 13 (87%) and Ukraine’s full alignment.

Most interestingly, Georgia did not align with EU human rights-related declarations dedicated to the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia (16 May 2022) and Human Rights Day (9 December 2022).

Both declarations specifically referred to the EU’s founding principle of protection of minorities, reflected in Article 2 of the Treaty (respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities). Alignment with these principles would have been vitally important given Georgia’s membership application in March 2022.

Georgia also decided not to join the EU declaration on the 10th anniversary of introducing the Law on Foreign Agents in Russia in July 2022. This decision was taken months before the ruling majority backed a similar legislative act on foreign agents in the parliament. The draft legislation was given very negative assessments by Georgia’s strategic partners. EEAS issued a statement, raising “serious concerns” about the draft law, which was finally voted down following a massive popular opposition and protests.

In addition, Georgia did not align with the following themes at all each time they featured in EU declarations:

- Restrictive measures (RM) against Belarus (8 declarations);

- RM against Burundi (1 declaration); Hong Kong (1 declaration);

- 4 RM against Iran and 1 declaration;

- Kazakhstan (1 declaration);

- RM against the Republic of Guinea (1 declaration);

- Russia (2 declarations);

- RM against South Sudan (1 declaration);

- Zimbabwe (1 declaration);

- Terrorism (1 declaration);

- Nord Stream (1 declaration);

- Human rights (3 declarations)

Georgia is clearly abstaining from having a position on practices that are authoritarian, undermine European and global security, or go against European values.

A Matter of Values

The contradiction between Georgia’s EU membership aspirations and unwillingness to follow the EU consensus on foreign policy is glaring. Tbilisi’s voting pattern clearly rejects a value-based normative approach to foreign policy and does not manifest any affinity to upholding the liberal world order. It is also paradoxical from the point of view of Georgia’s officially declared foreign policy documents and priorities: such as the convergence with European and Euro-Atlantic security institutions and eventual membership in the EU and Nato, but also from its declared foreign policy that declares Ukraine a strategic partner and Russia as an existential threat.

The Georgian foreign service seems only capable of maintaining the most basic strategic red lines – maintaining the support for the principle of territorial integrity and non-recognition of illegal occupation or annexation regimes.

This approach is short-sighted. The EU and the U.S. are championing Georgia’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. The liberal, rules-based world order is the conceptual and legal foundation that allows Georgia to gain international support for its non-recognition policy of its occupied regions.

Divergence from the principled support of its strategic partners and allies and limiting its foreign policy to the defense of the narrowly defined self-interest saps the trust and confidence of the allies, which will take great effort and considerable time to restore. This will likely have lasting repercussions for Georgia’s long-term security.

The EU High Representative Borrell said when speaking to China that “neutrality in the face of the violation of international law is not credible.” The same undoubtedly goes for other countries as well.

This article is based on research carried out as part of the EU co-funded project – Caucasus University Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence for EU Policy Transposition (EUPOLTRANS).