RFE/RL Report on Georgia Re-Exporting “Dual-Use” Products for Russia Stirs Controversy

Concerns are growing over Georgia’s increased imports of “dual-use” goods from the West, along with exports to CIS states, since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The statistics raise the question of whether Georgia is acting as a transit state, providing sanctioned goods for Russia to use in building military equipment and weapons.

Over the past couple of years, the U.S. Senate, European research institutions, and the Ukrainian government have all expressed concern, while the Georgian Dream government strongly denies involvement in helping Russia evade sanctions.

RFE/RL‘s Tbilisi bureau published a detailed examination of statistical data on Georgia’s imports and exports over the past two years, drawing parallels to the document prepared for the US Senate, which shows that the “critical components” needed for Russia’s military operations may be passing through Georgia.

From the U.S. to Russia, with a Pitstop in Georgia

RFE/RL shared the February 21 document prepared by the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations entitled “U.S. Technology Fueling Russia’s War in Ukraine: How and Why.” The document is based on the foreign trade statistics of four major American technology companies – Intel, Analog Devices, AMD, and Texas Instruments. The microchips and semiconductors produced by these companies are often found by Ukrainian officials in Russian military equipment.

During the U.S. Senate hearing held on February 27, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn) argued that the U.S. technology breakthroughs are sustaining Russian belligerence in Ukraine. “American manufacturers are fueling and supporting the growing and gargantuan Russian war machine…The Russians are relying on American technology,”- he said, concluding: “Our exports control regime is lethally ineffective, and something has to be done.”

“Although our inquiry is ongoing, our initial findings show that those third-party intermediaries located in countries bordering Russia are used to evade U.S. export controls,” Sen. Blumenthal added.

According to another Senator, Republican Ron Johnson, “based on preliminary information,” the non-sanctioned countries, including Armenia, Finland, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Turkey, appear to be “legally importing military components from the U.S. and then either directly or indirectly exporting the semiconductors to end users in Russia.”

Microchip export data from American companies

| Importing Country | 2021 | 2022 | Percental Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | 13,259 | 372,414 | 2709% |

| Finland | 86,435,802 | 140,633,056 | 63% |

| Georgia | 375 | 13,014 | 3370% |

| Kazakhstan | 1,936 | 1,918,771 | 99010% |

| Turkey | 14,523,007 | 31,574,164 | 117% |

Source: RFE/RL

Apart from the ready-made microchips, semiconductors are crucial for Russia. They are used to build Russian military aircraft, rackets, armored vehicles, and communications systems. RFE/RL points to a CNBC analysis showing that Russia imported $2.5 billion worth of semiconductors in 2022, almost twice as much as the previous year. The countries supplying the product to Russia are suspected to be China, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Russia’s neighboring states (Kyrgyzstan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Armenia).

RFE/RL also looked at the KSE Institute’s report, which emphasizes that by the summer of 2023, Russia had fully restored imports of “critical components” needed for its military operations, increasing its product supply to almost pre-sanctions levels thanks to third-country intermediaries. In 2023, Russia also imported $1 billion worth of Western microchips.

Looking at statistical data published by Georgia’s National Statistics Service, RFE/RL found that in addition to microchips and semiconductors, imports of other “critical components” needed to bolster military armaments have also increased. For instance, exports of radio navigation equipment to CIS countries have surged. In 2023, 80% of Georgia’s radio navigation systems exports went to Azerbaijan, with 11% to Turkmenistan. Before 2022, such exports to Turkmenistan hadn’t occurred, and the total exported to Azerbaijan from 2016-2022 was a quarter of the 2022 amount.

Georgia: Transit Hub for European Goods to Russia?

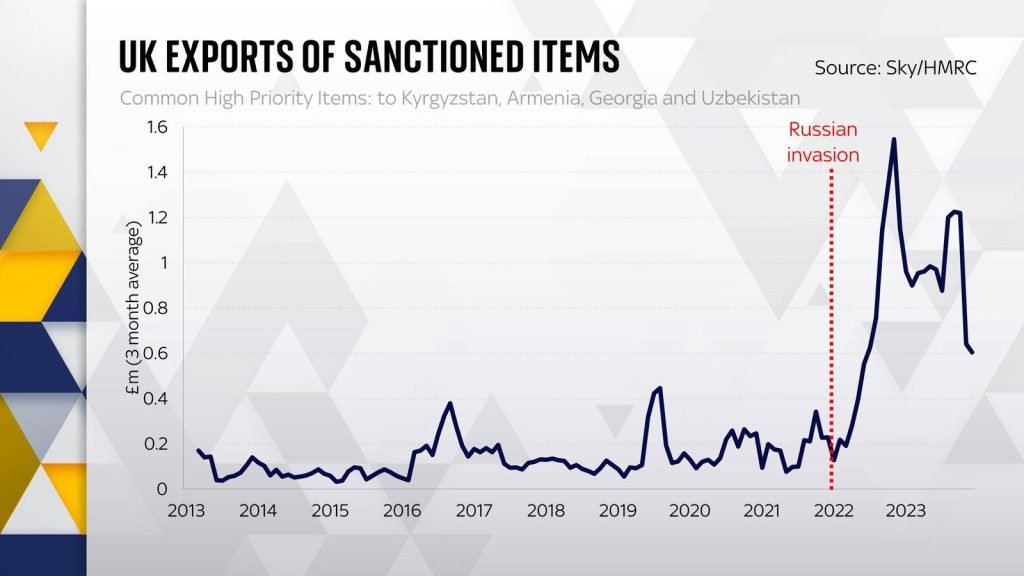

In a separate investigation, British news channel Sky News found that British companies have significantly increased exports of equipment and machinery that can be used for military purposes to Central Asia and Caucasus countries, “undermining the official sanctions regime and bolstering Vladimir Putin’s war machine.”

Sky News points to the data, which shows a 74% drop in direct British exports to Russia after 2022. However, looking at the “common high priority items” – the EU’s list of 45 categories of goods found in the battlefield remains of Russian weapons – their exports to four Caucasian and Central Asian states have soared, increasing by over 500% since the outbreak of war.

Britain’s main exports to Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Georgia, and Uzbekistan are parts for drones, planes, and helicopters; data processing equipment; telephone switching equipment; aeronautical navigation equipment; and radio navigation aids.

Georgia Refutes the Allegations

In a social media post, Finance Minister Lasha Khutsishvili called the RFE/RL article a “manipulation aimed at misleading the public and damaging the country’s image.” He stressed that the statistical data used to argue that Georgia is helping Russia circumvent sanctions doesn’t give the full picture, as it only shows imports from one country – the United States – and doesn’t take into account the effect of COVID-19 on Georgia’s economy, which led to a sharp fall in imports which have been taking off after the pandemic.

The Minister points out that some of the indicators that are presented as high in comparison to 2021 are, in fact, very low if we compare them to pre-Covid figures. For example, RFE/RL wrote that the import of tools and instruments necessary for aeronautical or space navigation from the U.S. has increased sixfold. Khutsishvili states that, in reality, the total import of these goods has decreased 14-fold compared to the pre-COVID period (2019), from USD 2.6 million to a mere USD 180 thousand.

“Effective control mechanisms against sanctions evasion have been fully implemented in Georgia, and our partners imposing international sanctions have been fully informed about it,” – said the Finance Minister, adding: “The period mentioned in the article was evaluated by international sanctions coordinators during their visit to Georgia, and the systems implemented by Georgia for the enforcement of sanctions received a high rating, which was also publicly announced.”

As for the allegations made during the U.S. Senate hearing, Khutsishvili noted that the Revenue Service of the Ministry of Finance of Georgia has already asked for clarification and evidence from the U.S. counterparts. “The Ministry of Finance is in close cooperation with all US sanctions enforcement agencies, and we have not received (and are still awaiting) any information that would in any way confirm the assumptions made.”

The Minister states that “no country is doing more than Georgia (not only in the region) in the direction of enforcement of international sanctions” and emphasizes that “it is time to put an end to this orchestrated campaign of slander and to give due credit to Georgia’s efforts in the global issue of enforcement of international sanctions.”

A Look into Official Data

We have taken a look at the official statistical data on imports into Georgia of “dual-use” goods that could be transported to Russia. The data presented in the tables below can be found at the Foreign Trade Portal of the National Statistical Service of Georgia.

When comparing the years, we took into account the COVID-19 pandemic factor and didn’t include data from 2020, when Georgia’s foreign trade fell sharply. Therefore, the volume of imports is compared between the pre-pandemic period (2019), the pre-war year (2021), the year the war started (2022), and the following year (2023).

Regarding electronic integrated circuits and microassemblies imported to Georgia, we compared imports over the years and specifically how imports from the U.S. and the world fluctuated.

Electronic Integrated Circuits and Micro-assemblies

| USA | World (total) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 0.01 tons ($ 4 680) | 16.13 ($9 813 970) |

| 2021 | 0.02 tons ($2 260) | 14.56 ($4 029 470) |

| 2022 | 0.03 tons ($39 030) | 12.66 ($4 119 770) |

| 2023 | 0.02 tons ($19 250) | 14.96 ($3 564 790) |

The table below shows how the number of Common High Priority Items imports changed before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The list of Common High Priority Items is divided by the EU into four tiers, containing a total of 50 (Harmonized System codes) dual-use and advanced technology items sanctioned under the Russia Sanctions Regulation and involved in Russian weapon systems used against Ukraine, including the Kalibr cruise missile, the Kh-101 cruise missile, the Orlan-10 UAV and the Ka-52 “Alligator” helicopter.

Imports of Common High Priority Items (Tier 1 and Tier 2)

| 2019 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic integrated circuits; processors and controllers, whether or not, combined with memories, converters, logic circuits, amplifiers, clock and, timing circuits, or other circuits | 5.90 tons ($4 078 420) | 3.16 tons ($1 285 390) | 2.65 tons ($606 670) | 3.33 tons ($1 929 470) |

| Electronic integrated circuits; memories | 2.67 tons ($735 330) | 1.63 tons ($387 640) | 2.64 tons ($592 520) | 1.81 tons ($332 350) |

| Electronic integrated circuits; amplifiers | 0.05 tons ($94 350) | 0.05 tons ($8 010) | 0.19 tons ($8 360) | 0.15 tons ($11 200) |

| Electronic integrated circuits; n.e.c. in heading no. 8542 | 6.67 tons ($4 427 010) | 9.63 tons ($2 324 150) | 5.95 tons ($2 215 440) | 9.49 tons ($1 269 310) |

| Communication apparatus (excluding telephone sets or base stations); machines for the reception, conversion and transmission or regeneration of, voice, images or other data, including switching and routing apparatus | 404.15 tons ($37 142 610) | 316.47 tons ($34 787 470) | 450.16 tons ($62 552 080) | 390.57 tons ($60 594 190) |

| Radio navigational aid apparatus | 8.12 tons ($1 076 330) | 3.25 tons ($970 150) | 5.38 tons ($1 491 980) | 7.14 tons ($1 364 870) |

| Electrical capacitors; fixed, tantalum | 0.05 tons ($189 610) | 0.00 tons ($1 740) | 0.02 tons ($12 670) | 0.00 tons ($190) |

| Electrical capacitors; fixed, ceramic dielectric, multilayer | 0.02 tons ($5 590) | 0.05 tons ($2 460) | 0.11 tons ($5 670) | 0.23 tons ($6 670) |

| Electrical parts of machinery or apparatus; n.e.c. in chapter 85 | 0.16 tons ($2 710) | 0.04 tons ($7 490) | 0.02 tons ($910) | 0.21 tons ($17 880) |

Conclusion

Looking at the official statistical data, there is little evidence that the Georgian government increased imports of certain “dual use” commodities after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. If we compare the number of imports after the invasion and before the COVID-19 pandemic, we can see that, in most cases, imports have not even fully returned to pre-pandemic levels. However, this is only part of the official data we have examined, and the picture is much broader and more complicated.

There may be many reasons why the increase in imports appears to be significantly higher than it is. Comparing data from 2021 and 2022 doesn’t take into account the fact that 2021 was still the year when the Georgian economy was still recovering after the pandemic shock. The increase in imports in 2022 can thus be attributable to the recovery but also to the effect of the war in Ukraine. The contribution of each of these factors is hard to establish based on statistical data alone.

Also, in many cases, comparing the USD spent on imports over the years may be misleading since this does not take into account the price fluctuations. There are multiple indications from the producers and consultancies (examples here, here, and here) that the war has driven the price of semiconductors up due to supply chain problems and raw material shortages.

Nonetheless, there is an apparent spike in the import and re-export of “dual use” goods to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, and Azerbaijan – after 2022. However, linking the impact of this on Russia’s sanction evasion seems to require further detailed study and investigation by the relevant authorities.