Despite reforms, debts and evictions plague Georgians

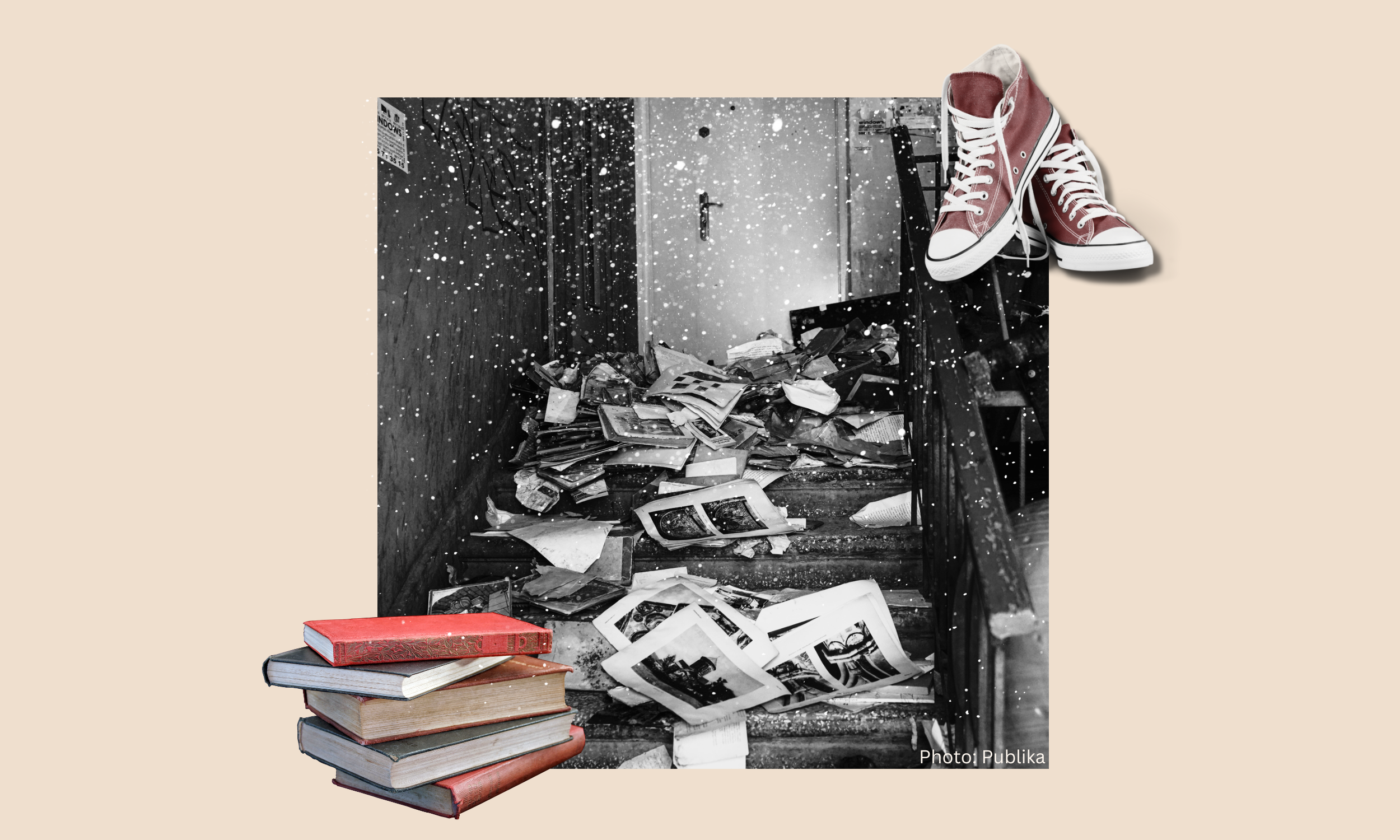

On January 23, Tbilisi saw its first long and steady snowfall of this winter. By a dark coincidence, it was also on that day that authorities had scheduled the first in a series of planned evictions in the city. Three families risked losing shelter in the cold. As the emotions ran high, there was a nagging feeling that the predatory lending system circumvented and survived relatively recent reforms, which were meant to protect citizens from precisely such occurrences.

From the early hours, dramatic scenes unfolded in Tbilisi’s Vake district. Activists and supporters had gathered to thwart the attempts of enforcement officers and police to evict Marina Khatiashvili’s family. The images looked familiar – it marked the fifth eviction attempt for this particular family as Khatiashvili struggled to cover her ballooning debt. Following hours of clashes, arrests of some activists, and use of force, authorities finally forced the family to vacate the apartment.

The confrontation caught public attention, sparking a debate about the causes. Some commentators focus on systemic problems with debt creation and high interest rates. Others say the private debt is doing such damage because citizens often lack financial management skills and exercise poor judgment. Yet, a more general consensus seems to be forging that unfair lending practices are widespread and that something needs to be done to curb them.

Experts argue that even though some reforms have tried to address Georgia’s longtime over-indebtedness problem through banking regulations, legal loopholes gave private lenders the space to exploit the lingering economic desperation.

According to Khatiashvili, her ordeal started back in 2008. She took a USD 20,000 loan from one of the top Georgian banks to cover her ongoing expenses. She hoped to pay it back with her salary but lost her job. A delay in payment got her in trouble with the bank. The bank, she says, then referred her to a notary who, in turn, connected her with private moneylenders. She was trapped.

“I had an initial loan of USD 20,000, which I’d pay back to Bank of Georgia and had already paid back up to USD 23,000 [of prime plus interest by 2013],” Khatiashvili told Mautskebeli, an online media outlet, in 2022. “As of today, from what I have counted – and I haven’t accounted for everything – I have already paid up to USD 83,000-84,000 to the system [of lenders].”

Khatiashvili’s account describes a scheme where private lenders get desperate borrowers handed down from the bank. They underwrite high-interest, short-term (up to six months) loans. With intermediary fees and high interest rates, the payments skyrocket and the borrower ends up in a losing rat race. Failure to pay one lender sees the borrower handed over to another. The immovable property is used as a collateral. Ultimately, Khatiashvili claims her only apartment ended up auctioned and bought by the same lender at an unreasonably low price of GEL 40,000 for a 108 square meter apartment in a prestigious Tbilisi district, where the market price for a similar place is at least three times higher.

Khatiashvili says she was willing to negotiate the complete repayment of the loan further, but the lender is inclined to keep the far more valuable apartment to make the most of the deal. The lender’s attorneys claim, on the other hand, that the lender bought the apartment in an auction for GEL 106,000 and settled Khatiashvili’s outstanding debt of $15,000, even offering to gift her another apartment as a gesture of goodwill. Khatiashvili distrusted the offer, pointing at laws allowing the cancellation of gift deals within a year.

Khatiashvili’s story may look complicated, yet those familiar with the trend say it’s far from an isolated case. Other borrowers, too, are reported to be paying back two or three times more than their initial loans to lenders and still risking losing properties that far exceed the borrowed amounts in value.

Deregulation, reregulation, loopholes

In the past decades, Georgians grew increasingly indebted. Experts trace the problem to the mortgage boom that started in the 2000s. It followed the 2003 Rose Revolution and the deregulation it brought. Those reforms, largely in 2007-2008, included eliminating the upper limit of interest rates on loans, abolishing individual bankruptcy laws, and laying out legal procedures for handling bad debts.

In a recent podcast with Mautskhebeli, Ia Eradze, a political economist, listed several factors that helped blow the mortgage bubble. The financial literacy among the Georgians was low; the country’s banking sector displayed oligopolistic tendencies; the access to capital for banks has improved, fuelling risky lending practices, including in foreign currency. Loans were aggressively advertised, and high levels of home ownership provided fertile ground for a mortgage boom.

“More than 90 percent of the [Georgian] population possessed housing,” Eradze wrote later on Facebook. “This is how [the primary source of] social-economic security turned into an attractive mortgage collateral for the banking system, this is how 2005 marks the start of the credit boom, and this is how a large part of the population was left on the verge of impoverishment.”

Local and international watchdogs sounded alarms about accumulated debts. In 2017, a blog of the ISET Policy Institute pointed to the “over-indebtedness trap.” Disturbing data showed 680 out of 1000 adults in Georgia had loans, the second highest rate in the world, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The issue peaked in 2018, when – weeks ahead of presidential runoffs – the government unveiled a plan to write off bad debts. It was then revealed that, in a country of 3.6 million, 600,000 persons were blacklisted by banks for bad debts.

At about the same time, gradual reforms reintroduced regulations on loans to combat over-indebtedness. Those in the private lending business were now obliged to register with the National Bank, while commercial banks, along with registered lenders, were required to assess the solvency of their clients before granting loans. Upper limits were imposed on effective interest rates and fines for delayed payments. Private lenders were also restricted from lending in foreign currency or through mortgage agreements.

Yet lenders found a way to circumvent the new restrictions: lending money through purchasing the real estate from a borrower with a buyback clause, often at a disproportionately low price. If borrowers fail to pay back their loans and interest rates on time, lenders retain the ownership of the property they’ve acquired for significantly less than its market value.

Data from public notary records obtained by lawyer Davit Kldiashvili, show the number of such buyback agreements grew eightfold in the 2.5 years after the new legal restrictions entered into force.

Battling indifference

The persistence of over-indebtedness and credit traps can quickly condemn vulnerable families to a life of self-perpetuating, downward-spiraling poverty. In a developing economy like Georgia, a health emergency can leave a person struggling with crippling debt for decades.

Many blame current predatory lending practices on indifferent government and inconsiderate courts. Allegations have also been made in the past days that greedy private lenders might enjoy connections in the government, judiciary, and banking sectors.

Legislative changes have also done little to end inhumane and degrading forms of eviction. According to Komentari, a Georgian analytical platform, in 2016 the power to evict was transferred from the police to the courts. Yet judges often focus on property rights in their reasoning and fail to consider proportionality, individual circumstances of borrowers, and the overall fairness of the measure. Timing and environmental conditions such as winter temperatures are often not taken into account when planning eviction.

However, the borrowers also might have protections. Kldiashvili told Netgazeti that if borrowers go to court, judges can declare the buy-back agreements null and void. Still, there is a disagreement on how coherent the court’s practice is in this regard.

The current debate exposed diverging views on striking the right balance between the rule of law, property rights, and human dignity. Those on the right-libertarian side, such as Giga Bokeria of European Georgia, have argued against further regulation, claiming that it was the banking regulations in the first place that pushed borrowers into the hands of less scrupulous – and less regulated – private lenders. “Everyone lobbying for additional restrictions today shares the responsibility for what will happen in the future,” Bokeria wrote on Facebook.

Others pointed out the lack of social and housing policies that leave the most vulnerable unprotected against hardship and greed. Left-wing progressive voices have criticized Georgian political parties for continuously neglecting social issues like these. There have been calls for an immediate moratorium on evictions before systemic solutions are found.

Anna Dolidze, an opposition politician, suggested a parliamentary commission must be formed to investigate the matter. “The opposition needs to act and discuss the issue because there is also a big mafia involved,” she said.

Georgia is due to hold parliamentary elections later this year, and social discontent could put more pressure on the government to do something.

Following the uproar, the authorities canceled the second eviction on January 24, citing the family’s ‘social vulnerability’ as a reason. On January 25, Khatiashvili also confirmed to Publika that soon after her eviction, she negotiated a deal with the lender to keep her apartment, against the payment of USD 90,000 within a month.

Yet it remains to be seen whether it’s a relatively happy resolution or another loop on a downward spiral for that family.

Nini Gabritchidze, Civil.ge