Nationalism and ideology in present-day Georgia: Interview with Prof. Stephen Jones

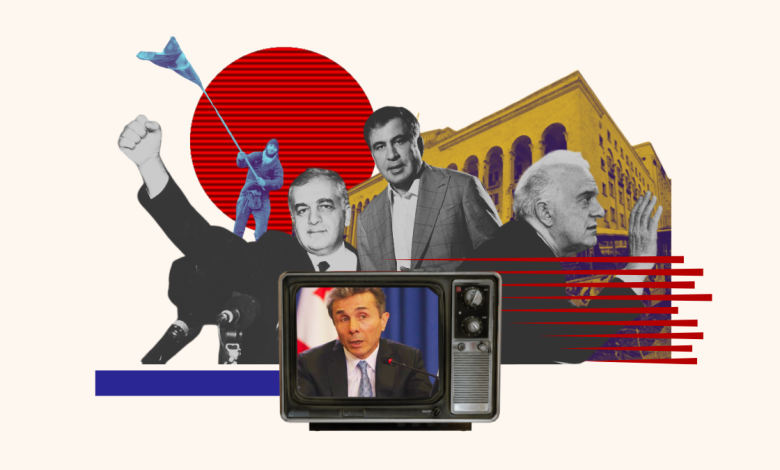

In an interview for the second edition of Civil Journals, the recently launched Georgian-language magazine, our own Nini Gabrichidze engaged in a thought-provoking conversation with Professor Stephen Jones, the distinguished head of the Georgian Studies program at Harvard University.

With a decades-long scholarly career, Professor Jones has immersed himself in Georgia’s history and politics, producing seminal works. His renowned book, “Georgia: Political History since Independence” (I.B. Tauris, 2012), meticulously dissects and analyzes the pivotal events that have shaped the nascent state. Like his other literary endeavors, the professor’s work examines Georgian politics, displaying a delicate balance between critique and empathy for the nation’s tumultuous journey.

Serving as a compass for those navigating the labyrinth of Georgia’s often contentious past, the book, regrettably, concludes its narrative in 2012, leaving readers in anticipation of how Professor Jones would interpret subsequent developments within his analytical framework. In a virtual interview via video call, we posed probing questions to Mr. Jones, drawing inspiration from his written works and the ongoing political landscape in Georgia.

As the current issue of our magazine explores identity, citizenship, and the essence of being Georgian, we delved into Professor Jones’s perspectives on nationalism, ideology, and civic engagement in contemporary Georgia. His responses offer an insight into the multifaceted challenges and dynamics shaping the nation’s present-day socio-political landscape.

Civil Georgia: Professor Jones, we wanted to thank you for taking the time to share your insights with our magazine. In your book Georgia: Political History since Independence you talk about nationalism in independent Georgia, which, as you say, has been marked by continuities and discontinuities. You describe Georgia switching from more “exclusionary” nationalism under Zviad Gamsakhurdia to “elite-managed” nationalism under Eduard Shevardnadze and to “emotional but modernizing nationalism” under Mikheil Saakashvili. The book covers events until 2012. We will soon enter 2024, and Georgian Dream has been in power for over a decade. Where in the categorization of Georgian nationalism would you place Georgian Dream rule?

Prof. Stephen Jones: Nationalism is a broad concept. That’s why we need these adjectives. We have radical nationalism, ethno-nationalism, civic nationalism, and so on. Nationalism is a flexible concept, chameleon-like. Since the 19th century, the ideology has dominated all political systems. Look at what happened to empires. Nationalism, though often looking to the past, has great appeal in the present.

At some level, we’re all nationalists. Some of us are more tolerant than others, but it’s just part of the world we live in.

At some level, we’re all nationalists. Some of us are more tolerant than others, but it’s just part of the world we live in. I’m not saying that nationalism is always negative. In many ways, it’s quite understandable why it works – it creates positive features like solidarity among communities and frequently leads to greater liberty. It also informs the arts and can be an inspiration for creative work. It’s not always a bad thing.

But implicit in nationalism is exclusion because you are focusing on one nation – a nation that deserves first place in the state. This is always a temptation for politicians – including Georgian leaders – because it works. It is very effective at mobilizing people. When Zviad Gamsakhurdia came to power, nationalism was a very effective weapon because it focused on the enemy, external and internal. It played on people’s perception of themselves as victims. But nationalism does not always rely on a sense of victimhood; it can be based, as it was under Saakashvili, on a sense of mission and dynamism. That does not mean, however, that under Saakashvili we had a more tolerant system. Nationalism has gone through many configurations in Georgia, which is what I try to show in my book.

Georgian Dream is like almost every other Georgian political party I have witnessed in the last 30 years. It’s a nationalist party. It seeks privileged status for Georgians and promotes Georgian national culture. Why would it be different? Almost every nation seeks dominance in its “own home.” But GD is focused on what we might call “conservative nationalism.” Most nationalisms revere the past and its glories. Even Saakashvili, the great modernizer, looked for precedents in Georgia’s history to justify his decisions and policies. The retreat into history is a way to legitimize the present, but in many ways, it is also a defensive mechanism arming the nation against the modern world. Georgian Dream’s version of nationalism, which focuses on Georgian traditional values associated with the family, the church, and binary gender roles, is one that many Georgians share and believe in.

Georgian Dream’s version of nationalism, which focuses on Georgian traditional values associated with the family, the church, and binary gender roles, is one that many Georgians share and believe in.

There was a very interesting speech by Irakli Gharibashvili in May 2023 at [a Conservative Political Action Conference – CPAC] in Budapest. It was a GD manifesto. I don’t know whether Gharibashvili’s entire government shares his views. I think most politicians are more interested in successfully manipulating national images and ideas. Whether they actually believe in them is a different thing. Viktor Orban, a right-wing Hungarian nationalist, was Garibashvili’s host at the CPAC conference. Orban promotes values that challenge the liberal EU’s ideas of tolerance and equality. But Georgia and Hungary are not so unusual in the European context. There are many different Europes, and one of those Europes is a very conservative one that shares Georgia’s ideological turn to the right.

There are many different Europes, and one of those Europes is a very conservative one that shares Georgia’s ideological turn to the right.

We can see this in Slovakia under the new PM Robert Fico, in Italy under the radical right-wing prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, and in the Netherlands, where Geert Wilders’ anti-immigrant party is now the largest. GD is not an outlier – it’s part of the European mainstream, where non-traditional groups and movements are seen as a challenge to an idealized past and a conservative present. The “flipside” of Georgia’s conservative nationalism is the condemnation of LGBTQ rights and legal constraints on religious minorities, which don’t conform to the Orthodox view of the Georgia nation.

Civil Georgia: We want to ask you about the Georgian Dream’s motivation in this respect. Many wonder why they have switched to such a rhetoric. Georgian Dream’s conservative rhetoric was less intense in the initial years of its rule, but now it has become more and more prominent. What do you think is their key motivation? Is it a mere campaign trick to win over more conservative voters and crack down on their critics, or do you also see some solid ideological foundations there?

Prof. Jones: It’s all of those things. The last point that you make about it being ideological is a good point. This is something that we do not consider so much when we discuss the current government. Western leaders and analysts tend to pick up on the polarizing rhetoric and focus on the polemic about being pro-Russian or anti-Russian. If you’re pro-Russian, you’re a traitor, and if you’re anti-Russian, you’re threatening the stability and security of the Georgian political system. This obscures the ideological evolution of the Georgian Dream movement from an essentially moderate liberal party in 2012 to a right-wing and very conservative one today. Today, GD is firmly aligned with the Georgian Orthodox Church and its values. GD sees this shift as a way to cultivate the support of Georgians who continue to live in a state of insecurity – and see the world around them as a source of political and economic threat.

The shift is ideological but also a practical political strategy. GD is losing support among educated youth and citizens in central Tbilisi, but outside the city center, in Didube and Gldani [districts in the outskirts of Tbilisi] and places like that, or in the rural areas where the population feels more marginalized, Georgian Dream’s ideology and rhetoric can have significant appeal. Georgian Dream has its political base and controls much of the TV, which reaches into the living rooms of the population outside the city. However, the ideology cannot cover up the fact that the government right now has little strategy for the Georgian economy beyond creating conditions for foreign investment. This is not very different from Saakashvili’s economic prescriptions, although Saakashvili, as a modernizer, was focused on persistent reform and experimentation.

In many ways, the Georgian Dream is a continuation of Saakashvili’s regime – the same economic policies, the same emphasis on state power and executive authority. Saakashvili’s government, too, was hostile to Georgian civil society and had authoritarian aspirations. I’ve written about these patterns of authoritarianism in the Georgian political system in my book Georgia: A Political History. GD is a government like Saakashvili’s, which despite the existence of a political base, is essentially detached from the broad electorate.

GD is a government like Saakashvili’s, which despite the existence of a political base, is essentially detached from the broad electorate.

GD is a parliamentary phenomenon isolated from the needs of the Georgian population. I don’t hear any real proposals on how to end the deep poverty that exists among the majority of Georgians. This is consistent with Georgian political patterns over the last two or three decades.

Civil Georgia: You have also written about the effects of the language on democracy. In one of your pieces for Eurasianet, you say that language can have a destructive effect on democracy, including through practices of mutual labeling by political actors as ‘enemies’ or ‘traitors.’ And then, in this interview, you also spoke on how the conservative rhetoric of the Georgian Dream can alienate religious minorities as well. Georgian Dream does not usually explicitly target Georgia’s religious or national minorities. Like other Georgian rulers, they typically take pride in the diversity of Georgia. But the party does have a strong focus and, I would say, overemphasis on Orthodox values. Can you elaborate more on how this conservative rhetoric can affect the struggle of building a diverse, multi-ethnic society?

Prof. Jones: Georgia traditionally has been multiethnic, although over the last couple of decades, particularly since independence, it has become an increasingly monoethnic country. Non-Georgians find it difficult to get employment or access to education and leave. Young Georgians are also leaving in large numbers. This is not good for the well-being and future of the state.

What democracy needs is an inclusive political language that communicates to its citizens. You need a language that explains and informs. And, right now, the language we hear from the UNM and Georgian Dream is neither of those things. We have a political language that reminds me of the Soviet Union’s use of language, which aimed not to enlighten but to obscure reality – or to create a reality full of enemies and threats. We have similar rhetoric in Western states where language is used to demonize immigrants. The style of language in use today in Georgia creates scapegoats. It creates as well as isolates minorities. It’s not simply a reflection of what’s going on in society. Language shapes the political landscape. Language is very active and very powerful; it has such an emotional effect on us as human beings and voters. It has the ability to create quite a false political reality, which leads to simplistic solutions.

What democracy needs is an inclusive political language that communicates to its citizens. You need a language that explains and informs. And, right now, the language we hear from the UNM and Georgian Dream is neither of those things.

Extreme language also makes cooperation with the opposition very difficult. Some degree of political cooperation is fundamental to democracy. Good governance needs a strong opposition and an effective opposition. In Georgia, we don’t see that. The EU put polarization at the top of its 12 conditions for Georgia’s EU candidacy for a reason – the absence of political consensus will lead to a democratic crash in Georgia. There is currently a vast political and linguistic chasm between the government and its opponents. The sort of extreme language we see in Georgia today undermines the preservation of democracy.

Civil Georgia: In your work, you also focus a lot on the issue of civic participation. You often link civic engagement with the state of the economy or access to education, as mentioned above. Many citizens of Georgia have regarded this year as a successful year for activism. For example, we protested very effectively against foreign agent bills this March. There was continuous pressure on the government to do more to obtain the EU candidate status, where the prospects now also look good. These trends have kind of reignited in Georgia the faith in civic mobilization and the self-confidence of Georgians as active citizens.

You have been observing Georgian social and political dynamics for many decades. Do you think that things have really changed for the better in this regard? Or is the active participation still somehow obstructed by persistent inequalities and urban-rural or center-periphery divides?

Prof. Jones: Democracy requires protest- and thinking about the civil rights movement of the 1960s – the United States would be a good example of how protest contributes to democratic expansion. Sometimes, there is no other effective way of generating change – usually because of institutional conservatism or blockage of change through political reform. This is what we see in Georgia today – institutions are not working to bring citizens into governance. Over the last three decades, protest has been central to the development of Georgian democracy. The members of Georgian Dream just need to look at their own experience leading up to the elections of 2012. Protest is a response to the lack of accountability in government institutions. It reminds political parties of their obligations to connect with the needs of their constituents. Otherwise, they will be kicked out.

Democracy requires protest.. Sometimes, there is no other effective way of generating change – usually because of institutional conservatism or blockage of change through political reform.

Right now, elections are not working well for Georgians. They are not creating a fundamental condition for sustaining democratic governance – a responsive government and a responsive parliament. Georgia’s parliament has become symbolic of the absence of accountability in the system. The parliamentary building on Rustaveli is like a fortress. You have to get multiple permissions to get into these places guarded by barriers and policemen if you want to talk to your representative and express your point of view as a citizen. This is central to the problem – the psychological and physical chasm between the government and the population.

Georgia’s parliament has become symbolic of the absence of accountability in the system.

Protest is important, but it’s not enough on its own, of course, and violent protest can work the other way and shut down reform. What you want are political conditions that allow for citizen participation. The state of the economy plays a role in this. When you have two or three jobs and can’t provide for your family, you often don’t have the time or energy to participate as a fully involved citizen in the politics of your country. Poverty leads to political alienation. Statistics suggest that if you want to preserve democracy, especially among new and emerging states, then you should create conditions of greater economic equality and access. Right now, economic and educational opportunities for ordinary Georgians are limited. In rural areas, in particular, opportunities for economic advancement are poor. Economic opportunity increases the legitimacy and sustainability of open government and promotes greater engagement with civil life.

Interviewed by Nini Gabritchidze/Civil.ge

This post is also available in: ქართული