Jokes, Grievances and Demonstrations: Russians in Georgia and Germany

“What do the mobilizations in Israel and Russia have in common?” a Russian stand-up comedian asks the audience, “in both cases there are long queues for flights to Tel Aviv”. Almost everyone in the Bukhari stand-up bar in central Tbilisi laughs.

The author: Nico Butylin is a German journalist from Berliner Zeitung working with Civil.ge in the framework of the IJP Scholarship

For more than 90 minutes, several dozen – all Russian – people listen to the latest jokes from the Russian diaspora: swearing, mockery of Putin and the Russian homeland, but also mockery of the “Ruzzians Go Home” drawings in the Georgian capital.

After the attack on Ukraine in February and especially after the partial mobilization in the autumn last year, many Russians left their homeland. It is estimated that nearly a million people have left their country in the last 20 months – hundreds of thousands have fled to Georgia, and a few thousand have come to Germany. But there are serious differences between the Russian community in Georgia and in Germany.

In Georgia: a short-term stay in a bubble

While Germany has traditionally been a country of refuge – whether for Turkish or Italian guest workers, Poles, Russians or Romanians – the story is different in Georgia. Many Georgians have left their country in recent decades in search of better economic opportunities or because of political circumstances. But since the war with Russia, Georgia has itself become a destination for migrants.

The number of Russian migrants has risen from 15 percent to almost 50 percent – and this has made the social conflicts within Georgian society more visible. In the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, for example, not only have house prices exploded, but the cost of shopping in a supermarket or eating in a restaurant has more than doubled in some parts of the city. In addition, many Georgians have been burdened by the language situation since masses of Russians arrived in Georgia last year. Speaking the Russian language without being asked whether they know it is often described by Georgians as arrogant. There have also been allegations of physical confrontations between locals and fleeing Russians.

Walking around the places frequented by the Russian diaspora in Tbilisi, one thing stands out: Russians tend to stay in their bubble. They meet like-minded people at yoga classes, sign up for co-working spaces in Tbilisi’s trendy districts, or spend an evening at a stand-up comedy club. There are Russian schools, cafes, and reportedly even hospitals. But no one knows how long their bubble will last.

Most of the fleeing Russians don’t know how many months or even years they will stay in Georgia. “Maybe a year or two, depending on how the war goes,” says a Russian woman in a café near Tbilisi’s Liberty Square. Many of them hope that the war will soon be over, that Putin will fall and that they will be able to return home. With this assumption, many Russians remain in their bubble, have little contact with the majority society and, apart from Gamarjoba and Madloba, hardly learn the Georgian language. Almost everyone hopes that their stay in Georgia will be short.

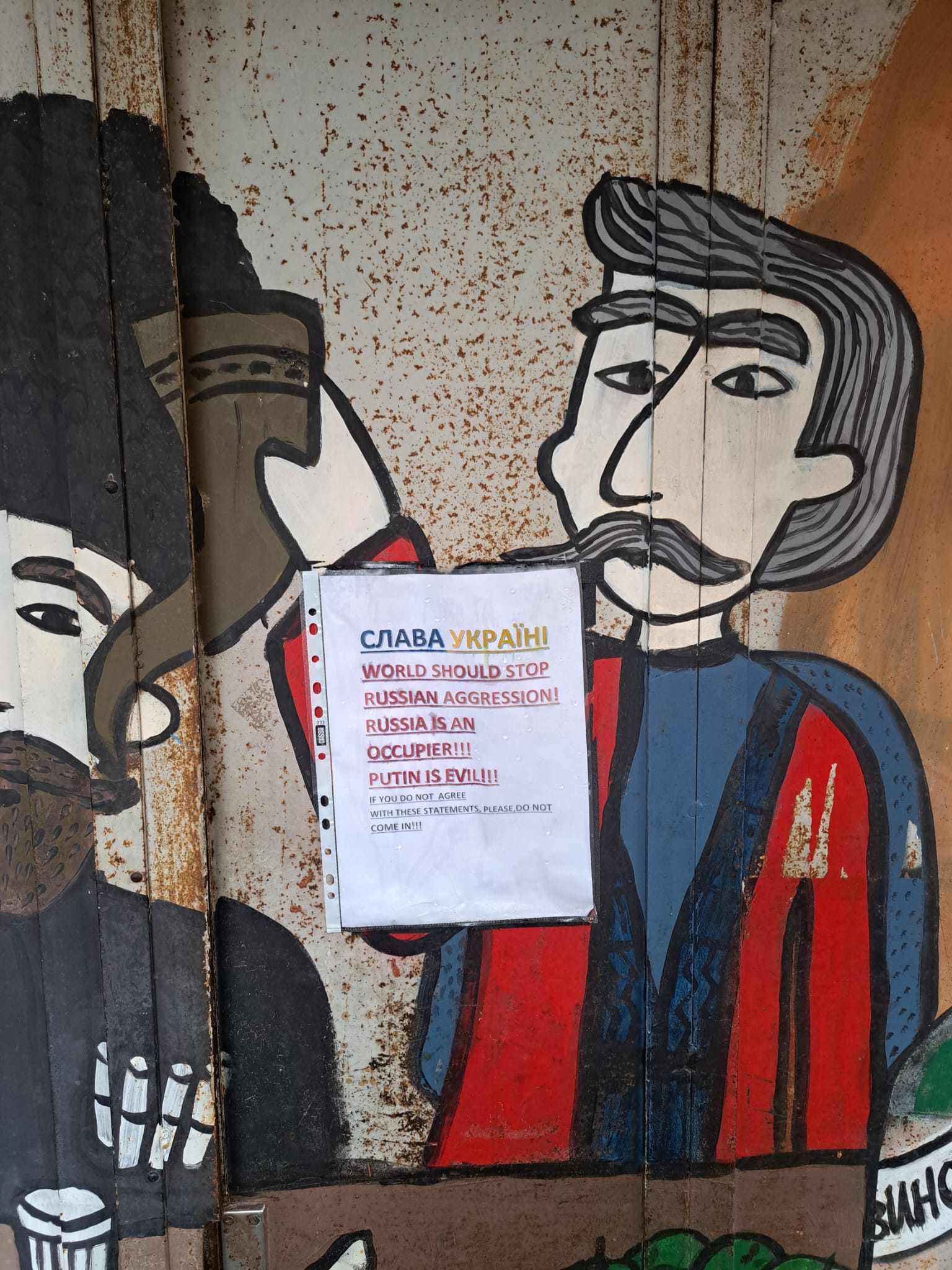

But things could heat up very quickly: from skyrocketing property prices in Tbilisi and Batumi to social tensions between Russian tourists and locals. The housing market is particularly tense in Georgia’s larger cities. “While an apartment in the Chughureti district with a nice view of the city cost between $250 and $300 before the war, it now costs more than $600 a month in some cases,” says a Georgian homeowner in Tbilisi.” The prices are almost the same as in Western European capitals. The numerous graffiti and stickers in the Georgian capital also speak a clear message.

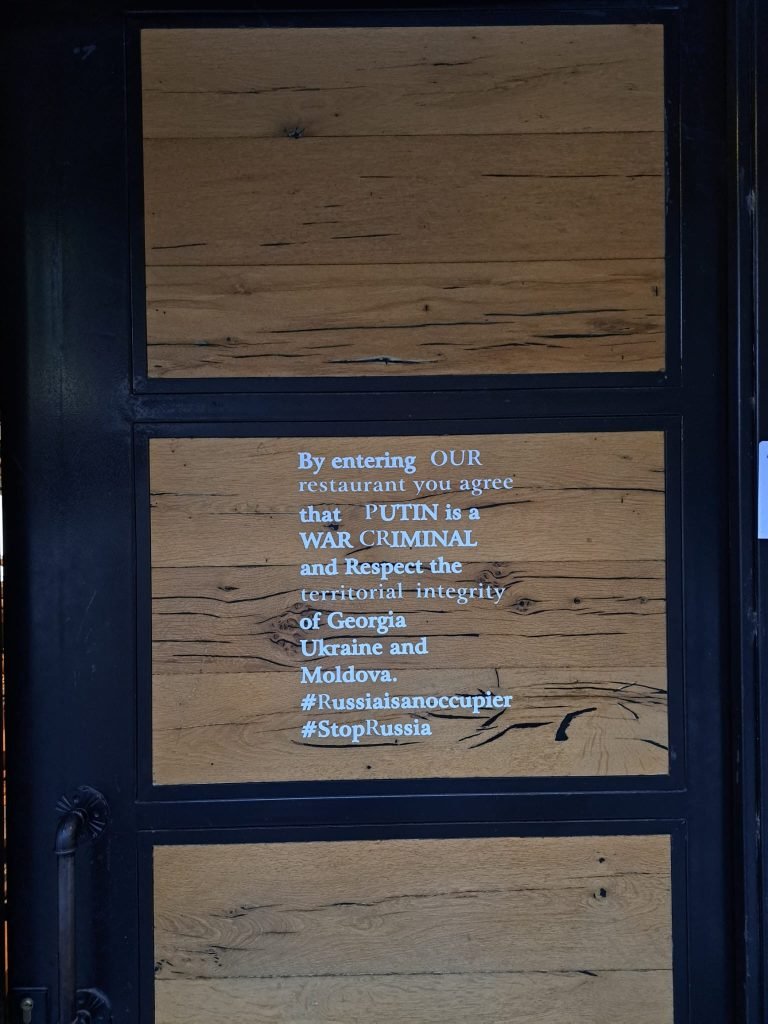

Moreover, Georgian restaurants and bars often try to point out that a stay in their country is based on their own rules. “By entering our restaurant, you agree that Putin is a war criminal and respect the territorial integrity of Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine,” reads a sign on the door of a restaurant in Stepanzminda. Another café in Dedaena Park in central Tbilisi asks customers to sign declarations saying they oppose Russian aggression in Ukraine and agree that Vladimir Putin is a war criminal.

Talking to Russians who have fled however, it is clear that they are aware that their homeland is associated with imperial behavior; to this day, 20 per cent of the Georgian state is occupied by Russian troops. The last war was only 15 years ago. This is another reason why many Georgians have doubts about the extent to which Russians should be welcomed with open arms. Discussions about visa restrictions, or a prevailing narrative that “Russians come to Georgia, stay in their bubbles, start businesses and send the money home”, reveal such negative attitudes.

In Germany: long-term stay and attempts to integrate

Germany, on the other hand, has a different basic premise towards Russian migrants in its history. Russians have come to Germany in several waves over the past 100 years – after the October Revolution, after World War II, during the GDR, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and now again after the attack on Ukraine. The number of Russians in Germany varies greatly, as the very heterogeneous group of Russian citizens, Russian-Germans, Russian-speaking people from Kazakhstan or Ukraine and Jewish-Russian refugees are often added together.

What is striking, however, is that Russians are often seen as ‘well integrated’ in German discourse. Many of them attend language courses, try to integrate into the majority society and hope to stay in Germany for a longer period of time. In contrast to Georgia, Germany is perceived by many Russians as a long-term place of refuge.

This also has something to do with the social structures in Germany: there is an established Russian community there. One is a political player, publicly calling for financial and military support for Ukraine, or seeing itself as the pro-European future of a post-Putin Russia. “Unlike in Georgia, Russians in Germany are less likely to be equated with the policies of the Putin regime,” says a Russian woman who sought refuge in Georgia and Germany after the war broke out.

On the other hand: what is unimaginable to happen in Georgia is the pro-war mobilization of a small part of the Russian-speaking community, like in Germany. Shortly after the start of the war, several car parades took place in Germany, the Russian tricolor was hoisted, and participants wore Putin and PMC Wagner shirts. Social tensions between pro-Putin supporters and their opponents around the Soviet monuments in Berlin were particularly high around 9 May. The Georgians were spared this. In fact Georgians in Tbilisi took part in or organized rallies to protest against Russia’s war in Ukraine.