Recently, a public debate emerged about how the candidates for school principalship are selected and then elected by the board of trustees at individual schools. The matter is significant in terms of crucial factors like transparency, equality, and human rights impacting the selection of individual candidates and the entire process. What is more, the choice of principals can also be seen in the broader context of the development of the country, its society, and the educational system. But this opportunity seems is being wasted.

Author: Shalva Tabatadze is the Chairman of the Centre for Civil Integration and Inter-Ethnic Relations. He specializes in education policy.

Why are school principals important?

The role of school principals is undeniably crucial for students’ academic success and overall well-being. Numerous empirical studies and longitudinal meta-analyses strongly support this assertion.[1] They reveal that school principals’ activities and instructional leadership may substantially increase students’ results. A highly effective principal’s impact is even greater than that of a highly effective teacher.[2]

But apart from this direct impact on the quality of education, the democratic election of school principals has broader implications. The process of electing school principals by the school community, which holds them accountable, and the participation of teachers, students, and parents in the decision–making process are essential attributes of democratic schools. Democracy in school leadership and management also contributes crucially to developing a democratic society.[3]

How does it work in Georgia?

The general education system of Georgia, which consists of primary, basic, and secondary levels, is managed at the central (Ministry of Education and Science), local (Education Resource Centers), and school levels. There are 2,085 public schools in the general education system of Georgia. School principals manage the public schools, the board of trustees, teacher councils, and student councils.

Georgia’s decentralization reform began in 2005 and resulted in democratically elected school boards of trustees. In 2006-2007, the school boards elected school principals in 53% of existing public schools. In 2007, 1,166 principals were elected out of 5,500 applicants. 85% of the elected principals had pedagogical experience, and only 15% entered the system without this experience.[4]

The decentralization reform of 2005 has also granted schools significant autonomy in human resources, finance, and instructional process management.[5]. The boards became responsible for electing the school principal, approving the school budget, and part of the school regulations.[6]. The decentralization reform has tasked school principals with managing the school administration and the learning process.

The second wave of decentralization and school leadership reforms occurred in 2012-2014. The Ministry of Education and Science adopted the School Principals Standard and instituted the certification process of the candidates for school principalship. 1,305 candidates were certified in 2012-2014. Of these 1,305 certified candidates, 746 were from self-governing cities (Tbilisi, Kutaisi, Rustavi, Batumi, Poti). The number of public schools in these cities is 275. Only 559 certified candidates are from other Georgian cities, towns, and districts, where 1757 schools are located, creating a shortage.

As a result, the practical application of the crucial function of the boards in electing school principals remained viable and pertinent only in major self-governing cities.

The Ministry initiated the third stage of school principals’ certification in 2020, with 3,200 applicants registering for the certification exam. But largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the exams were delayed until 2022, when only 1,839 of the registered persons took it. Out of these, 755 successfully passed and progressed to the interview stage. Following the interviews, 593 candidates were granted the certificate, while 162 were not.[7]

In the end, 1,409 certified candidates (593 newly certified and 816 candidates from the 2012-2014 wave of certification) registered to run for elections.

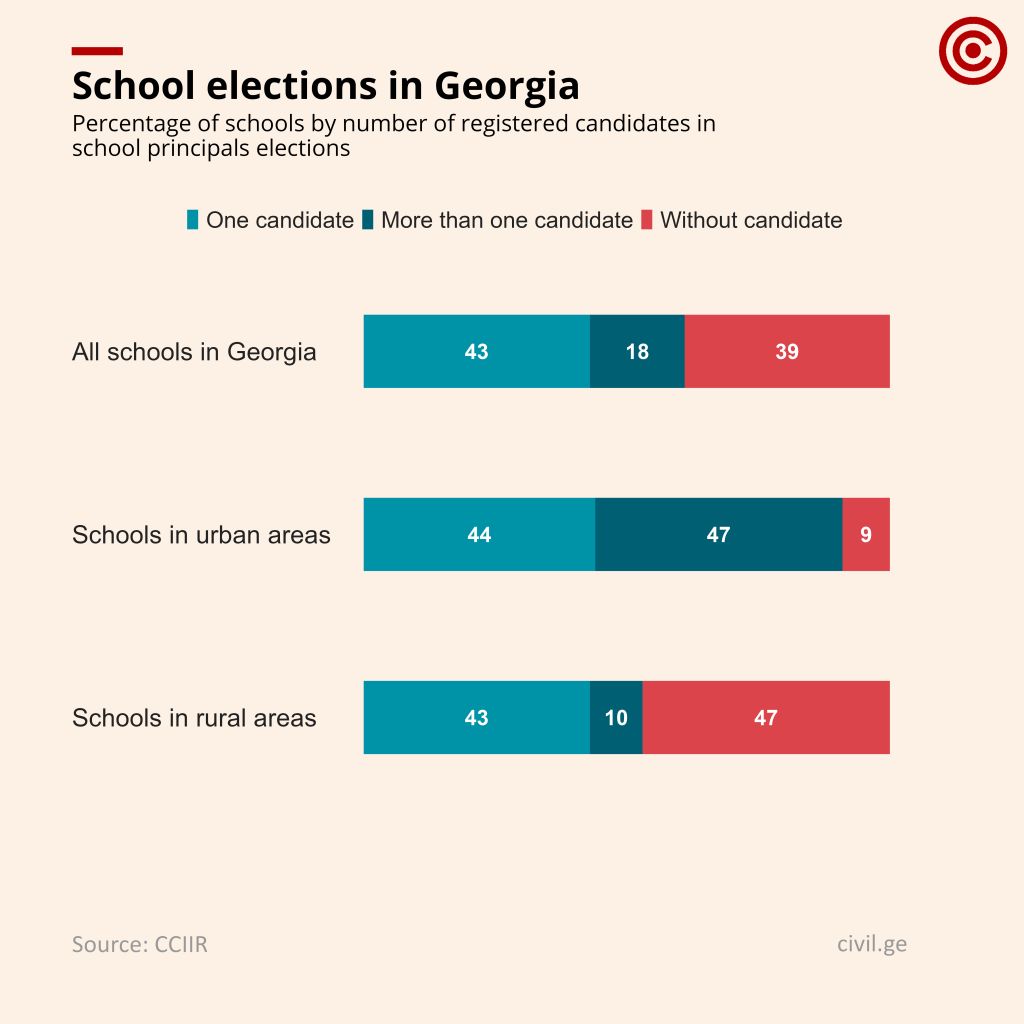

The candidates can choose which schools they would want to lead. Based on that primary choice data, only 382 public schools had more than one candidate registered.

Among them were schools with more than ten registered candidates – this was mainly the case in the capital city. However, most schools had only one candidate (894 schools) or no candidate willing to run for elections (798 schools).

The Ministry held the second round of interviews and approved only 927 applicants to stand for elections. The remaining 482 certified candidates were rejected, and their candidacies were not sent to the school boards.

As a result of the reduction of the number of candidates during the second round of Ministerial interviews, in 382 schools that previously had more than one candidate registered, the boards lost the ability to hold competitive elections. With few exceptions, the Minister left only one candidate per school.

The state of reform

This entire process showed two significant trends. Firstly, professional, motivated, and qualified candidates are no longer attracted to school principalship. There has been a sharp fall in the number of applicants to become a school principal. This likely means the current educational environment and opportunities do not attract a professional cadre. While it is often referred to, low pay is unlikely to be the determining reason. Since 2007, the comparative financial situation of the principals has not deteriorated, but there has been a notable decline in applicants.

Professional, motivated, and qualified candidates are no longer attracted to school principalship.

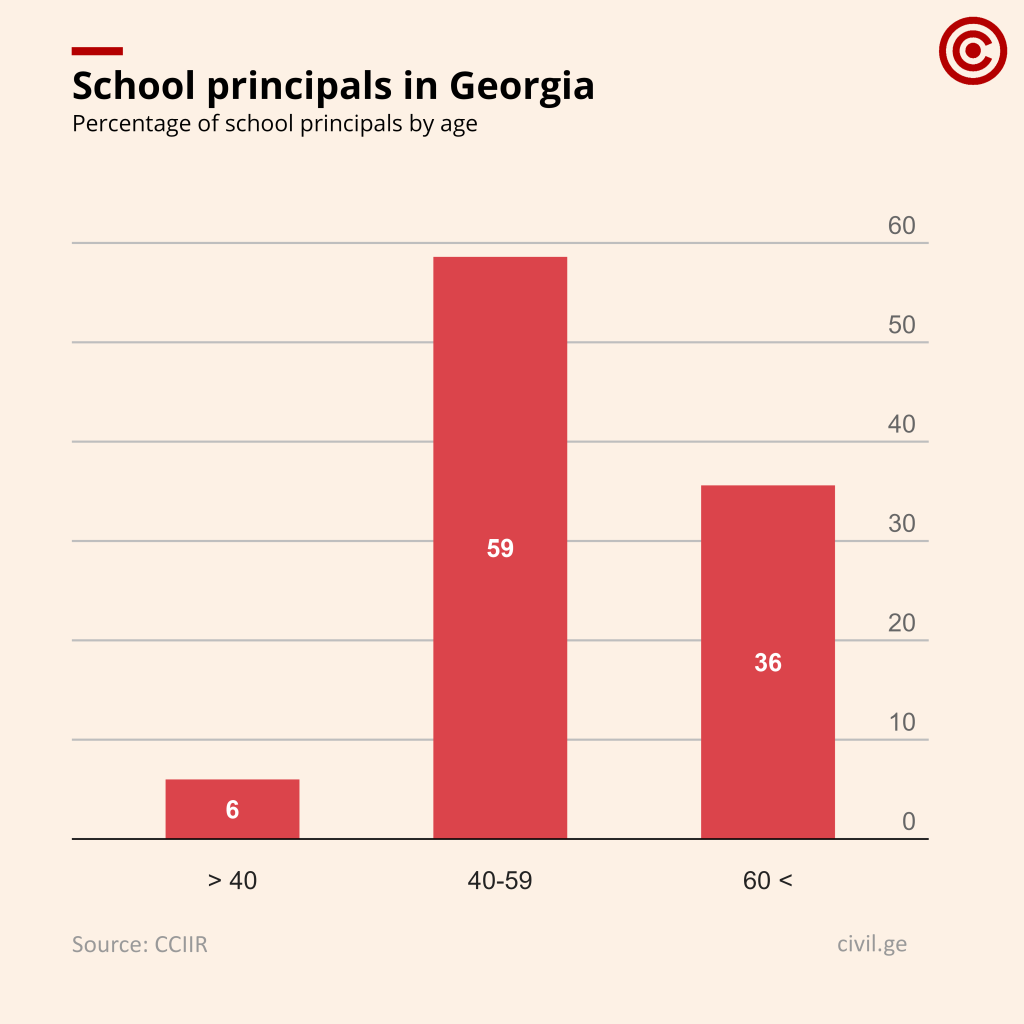

A look at the current statistics of school principals or acting principals shows that the profession does not attract young and qualified candidates. 35.9% of principals are over the age of 60, and the share of this demographic surged significantly since 2018. Similarly, only 8% of the principals were under 40 in 2018, and their share fell further by 2021 to 6%.

Personal observation and communication with candidates suggest this trend is due to the limited autonomy and lack of freedom within the profession. Bureaucratic procedures stifle the motivation and alienate enthusiastic candidates. Many young professionals became disheartened and no longer wish to re-enter the profession.

Secondly, the ambition of having democratic schools led by elected, professionally chosen school principals, has been abandoned.

The two-stage interview by the Ministry, the way it is institutionalized, is used to limit candidates’ ability to reach the election by the boards. Candidates who have passed certification exams and got high test scores are excluded from the process based on interviews for certification or interviews for selection as candidates for principalship. These interviews do not draw on objectively measurable criteria.

The intention of having democratic schools led by elected, professionally chosen school principals has been abandoned.

In the recent elections, 162 candidates were rejected from the certification interview stage, and 482 candidates were removed from the interview stage before being presented to the school board. Since all of the rejected candidates were certified, and since no formal criteria for the rejection exist, there is a reason to conclude that the procedure has been used, and may be used in the future, to eliminate candidates that are considered undesirable from the points of view that are other than professional.

The candidates filed no legal or administrative complaints about the certification testing. However, 27 out of 162 candidates rejected during the interview phase filed lawsuits.

In the way it has evolved and has been applied, the procedure has effectively excluded the school boards of trustees – composed of teachers, students, and parents – from participating in the decision-making and electing principals based on the school community’s needs. Students, teachers, and parents protested in many schools across Georgia, feeling deprived of the opportunity to select their principals following their shared vision for the school’s development.

After 18 years of reforms, we have ended up with an entirely undemocratic system for selecting and electing school principals, reminiscent of the Soviet era, where only one candidate is presented for election. Worse, in some cases, there are no candidates at all.

Even if the school’s board of trustees is dissatisfied with this sole candidate, according to the legislation, the Minister of Education and Science holds the discretionary authority to appoint anyone as the acting director, and this director does not have to be certified for principalship.

Consequently, this system deprives schools of the opportunity to select professional and qualified principals, granting political authorities the power to appoint them based on their subjective preferences. This undermines the school’s autonomy.

Enhancing students’ academic achievements through effective and professional school leadership or achieving democratic societal development and other important conferred by democratic schools thus remains a distant aspiration. The potential for more effective education seems to be wasted, while an additional stimulus to the country’s democratic development is fading.

[1] Waters, Marzano, & McNulty, 2003; Leithwood, Seashore, Anderson & Wahlstrom. 2004; Grissom, Egalite & Lindsay, 2021;

[2] Grissom, Egalite & Lindsay, 2021

[3] Council of Europe. Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture, 2018).

[4] Chanturia, Kadagidze, and Melikadze, 2020

[5] Education and Science Strategy 2022-2032

[6] Chanturia, Kadagidze, & Melikidze, 2020

[7] CCIIR Analytical Bulletin, 2023