Georgia should invest at least 5% of its gross national income and 14% of its budget in education if it wants to move up one level in the PISA index, which measures the performance of secondary school students and, thus, the quality of education. A significant portion of this money should be earmarked for primary and secondary education. But spending money is not enough to achieve the result we want – an educated and competitive society. For that, we also need a competent government ruling through democratic consensus.

Zurab Tchiaberashvili is a professor at Ilia State University

In all three categories of the 2018 PISA index, which examines students’ functional literacy, mathematics, and science, Georgia is at the lowest, first level. The main reason for this is that, according to the World Bank data for 2020, a student in Georgia formally spends 12.9 years in school, but this corresponds to only 8.3 years of quality education.

Moldova, Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, Ukraine, and Russia – these countries of our region, with whose citizens we have to compete, both individually and collectively, are scoring significantly better than Georgia and are in the second tier in all three PISA index categories, The Global Competitiveness Index also shows, that by 2019, Georgia lagged behind other countries in the world, including from our region, in terms of workforce skills (125th out of 141 countries), quality of staff training (123rd place) and quality of professional training (135th place).

We should begin to change this situation by getting out of the “cellar” of the PISA index and trying to move up, to the second level where most of the regional neighbors are. At this stage, it is pointless to compete with Estonia. Not only this country is in the top, third tier, but occupies a leading position, even ahead of some of the old democracies. Still, it is important to consider some elements of the Estonian experience.

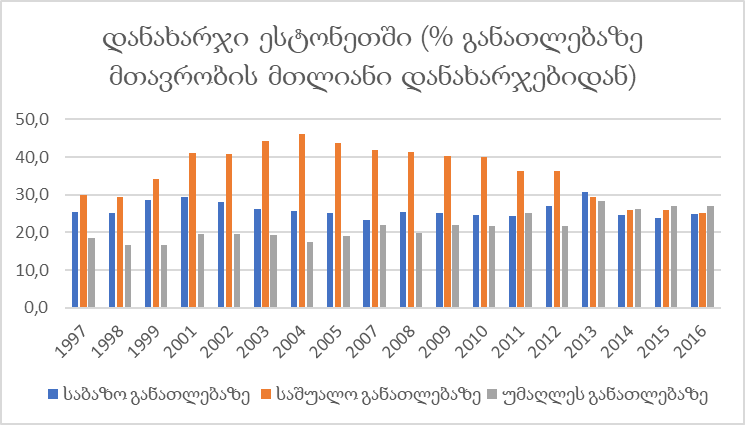

Looking at the graph below, compared to higher education (marked grey), funding for primary (blue) and secondary (orange) education in Estonia has been much higher, especially since the 2000s. It is only since 2015 that all three indicators have almost equalized. This means that Estonia has invested a lot in schools early on. The leading position in the PISA indices is one proof of returns on that investment.

One should not conclude that Estonia invested in education to move up some international index. This should not be Georgia’s objective, either. But the indices are an indicator, reflecting the success that the country and its citizens must achieve and should feel.

For example: from 2006-2010, Georgia’s significant progress in the Ease of Doing Business index was a result of the reforms implemented. Today, Georgia keeps its high position in the index, but it no longer is the “champion of reform.” Accordingly, its citizens believe that the country is on the wrong track.

If we compare the public funds spent on education in Estonia and Georgia, we can see that Estonia has consistently invested 5% of its economy in education, and Georgia – not even 4% (not to mention that these funds would be different in percentage ratio depending on the size of the economy). Education accounted for 14% of government spending in Estonia and 11% in Georgia.

The word “spending” is not really fit for education, hence the word “investment” I used above. The purpose of investing public funds in education should be:

- To recognize that participation in the educational process is a value in itself, and that participation in this process paves the way to other values necessary to become a democratic society.

- To build a society of educated citizens, whose members understand not only their individual, but also the public interest, and are conscious of the need to satisfy their individual interests by acting with civic responsibility and in solidarity with other members of society.

- As many people as possible should be equipped with the knowledge and skills that will help them realize themselves, to implement their own ideas. In doing so, they should not face inequalities related to financial and geographical barriers.

- Education itself should be an important sector of the country’s economy. We should see it not as a source of qualified human resources for other sectors of the economy, but as a successful, highly productive segment of the economy, in which people will want to be employed and invest money.

It is education that expands an individual’s scope for self-realization, and it is education that increases collective human capital. The lack of qualified human resources is one of the greatest obstacles (along with access to finance) for people to be able to successfully implement ideas through joint efforts.

In the conditions of a hybrid war waged by Russia against Georgia, as well as during global pandemics, an educated citizen is a pillar of resilience and public safety: a person who believes in scientific opinion and can find and process reliable information will hardly be misled by the propaganda based on the ideology of the occupying state.

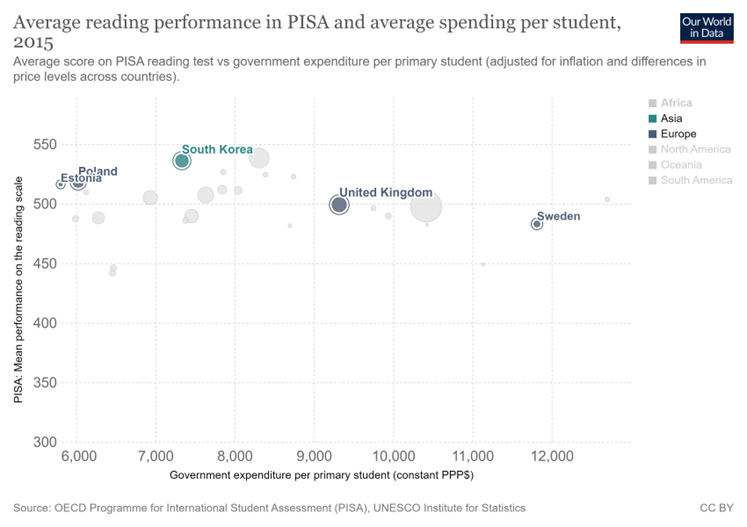

To ensure that the educational process produces such results, money is important, but it is only one of the factors. Chart 2 shows that Estonia, Poland, and South Korea lag far behind Britain and Sweden in terms of per-student expenditure, but their students are on par with British and Swedish peers in the PISA indices. In the security environment in which Estonians, Poles, and South Koreans have to live, educated citizens provide a solid foundation for security and resilience.

What lies beyond finance?

The government, no matter who is at the top, must realize that we cannot achieve results with centralized administration. It should create a framework within which all forms of education – formal system (school, college, university), informal but organized environment (training, camps, conferences), and socialization process (co-habitation, self-education) – will lead a person to the necessary skills, knowledge, and competencies.

It is most important that the formal education system is easily adaptable to the regional and infrastructural varieties of Georgia and to the changes in the global world. This underlines the importance of decentralization: administrative, financial, as well as according to forms of ownership. Of course, if we want the local self-governments to participate and to increase the adaptability of the system, the government itself must be decentralized.

All that we have mentioned here – the increase in funding and structural reform in education, and in general, the decentralization of governance, requires a normal, democratic process that produces a competent government from election to election and, despite differences, creates a consensus in the society around basic values and interests. Education must become the subject of such a consensus if we strive to maintain our place in this changing and competitive world.

In 2020, the population of Georgia was 3.8 million. According to the UN projections, it will be 3.4 million in 2050 and fall to 2.4 million in 2100. The decrease in natural growth is accompanied by an increase in emigration caused by poverty and a sense of hopelessness. Due to the lack of possibilities for self-realization and limited opportunities, Georgian citizens seek their future elsewhere. This further reduces the country’s human capital, which, as we said above, is the key to the country’s development and to overcoming the challenges it faces.

The collective understanding of this situation should nudge us toward change. Our biggest problem is that the collective understanding of this situation requires a certain level of education. Hopefully, Georgia has this resource.

Read also:

The views and opinions expressed on Civil.ge opinions pages are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Civil.ge editorial staff.

This post is also available in: ქართული