by William Dunbar:

I first met Giorgi Margvelashvili, Georgia’s recently departed fourth president, when he was a professor at GIPA in 2010. I was not impressed. Dishevelled, distracted, and with nothing much to say about building policy platforms for opposition parties, which was the subject of my research, and, theoretically at least, of his expertise.

When, three years later, I learned that he was the Georgian Dream nominee for president, and thus a shoo in, it confirmed some of my suspicions about the Ivanishvili style of governance.

He was to be a figurehead. A mere pawn.

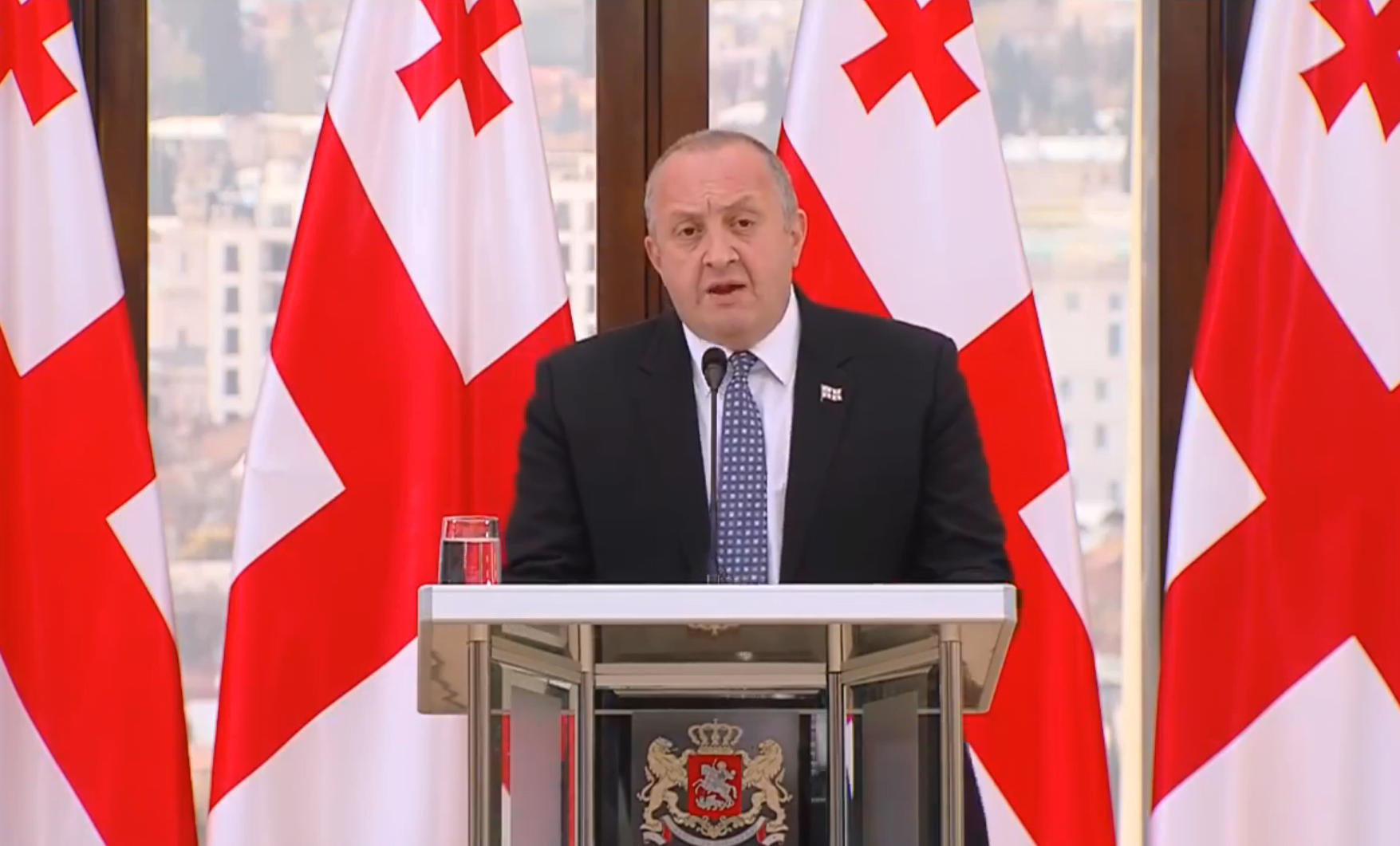

They cut his mad scientist hair, bought him a fancy suit, put him on poster and podium and told the people of Georgia to vote for him (which they did, handily). Georgian Dream wanted a puppet in the palace. How wrong they were. How wrong I was.

As he leaves the stage to return to his beloved potatoes in his mountain home of Dusheti, fair-minded people should give him a valedictory round of applause.

Giorgi Margvelashvili discharged his duties as president for the most part honourably and sensibly.

The subject of immense pressure from a government whose slide into corruption and dirty tricks got worse with each day he was office, he did his best to hold the line.

President Margvelashvili’s conflict with the government began on day one, when he stunned the world by defying the wishes of Bidzina Ivanishvili, his former patron and, rumour has it, philosophical debating buddy (wags say the secret is to disagree with Bidzina at first, and then be convinced by his powerful arguments).

As the former president tells it, following his inauguration he was shown into his new offices: a couple of rooms in the old state chancellery building. He was told to wait there while a new building was being refurbished. Unlike Ivanishvili, who eschews institutions and protocol, and does everything personally and through trusted underlings, Margvelashvili, perhaps naively, thought he would get to be a ‘real’ president, and took the office, and the trappings that come with it, seriously.

With that, he turned around and moved himself and his administration into the Avalbari palace, a giant, egg-shaped reminder of the Saakashvili years; and a building that, while of dubious architectural merit, is certainly a nice place to have an office.

It was a sign of things to come. For the duration of his presidency, Margvelashvili has been his own man. In a political environment where either slavish devotion or implacable hostility to Bidzina Ivanishvili are the orders of the day, the president’s independent frame of mind and honourable stances have been a welcome relief from the histrionics of both government and opposition.

The office he held was one stripped of most of its power by a constitution drafted during the UNM’s authoritarian third act, but for the most part Margvelashvili wielded his remaining tools wisely.

He vetoed numerous terrible pieces of legislation, including a surveillance bill that sought to legalise the government’s illegal snooping on our phones; a local government bill which undid a brief experiment with decentralisation, and deprived many of Georgia’s largest towns of directly elected mayors; and changes to the public broadcaster that put it more firmly in the government’s grip. All these vetoes were undone by parliament, but some of his changes squeezed through, and the principled way the presidency objected gave the lie to Georgian Dream’s accusations that its detractors were all Saakashvili loyalists.

More controversial was Margvelashvili’s use of the presidential power of pardon. With the aid of a professionally staffed commission, the president commuted or reduced the sentences of hundreds of prisoners—a necessary task given that, just like in the days of the UNM, Georgia once again has among the highest prisoners per capita in the world.

Most of those released were petty criminals, often those who had been convicted of victimless drug crimes. However, on at least two occasions individuals pardoned by the president went on to commit terrible murders. He will have to take this burden with him as he leaves office.

His appointments, too, were not always of the highest calibre. He waved through a Georgian Dream nominee for chair of the Supreme Court in spite of her deeply tarnished record (she has since resigned for putative health reasons). His refusal to cooperate with other political forces, notably Davit Usupashvili, and run for a second term in the last presidential election must also be held against him, but perhaps five years of having mud slung at you by the richest man in the country was more than anyone could take.

For many observers, the best thing about the Margvelashvili presidency was the composure of the man himself. Insulted, belittled and denigrated by his former party colleagues on a day-to-day basis, he shrugged it off.

While Georgian Dream’s attack dogs were set upon him, he responded with a calmness and dignity rarely seen in Georgian politics: many of those who criticised him regularly find themselves in humiliating brawls in the chamber of parliament. He also deserves credit for trying to be a nice guy.

When, in 2016, several politicians who had recently fallen out with Bidzina Ivanishvili were threatened with having intimate videos released, Margvelashvili’s response was both magnanimous and progressive. “Sex and sex life is not a shame,” the president averred. “I have sex, I’ve had a very rich sex life and will have it in future too.” When Georgian social media erupted in scorn over the national team’s traditional dress-inspired outfits for the Rio Olympics, he and his wife posed for photos in the much-derided costumes.

Margvelashvili is not a man born for high office. He won the presidency because Ivanishvili told the people to vote for him. But, were it not for his determination to be a real president and not a puppet, Georgia would have lost a valuable voice of moderation, and there would have been one less obstacle on the way to Georgian Dream’s complete consolidation of power.

His even temperament and liberal instincts are exactly what Georgia needs more of. As Georgia stares at a future of still deeper polarisation and ever-louder hysterics from two teams of mostly disgraced politicians, I wish there were more people cut from Margvelashvili’s cloth.

Or do I mean knit from his yarn?