The Hope That Never Dies

Nineli Andriadze, caretaker of Missing Persons Museum in Tbilisi, shows album of missing persons. Photo: George Gogua

Bella Zaldastanishvili’s world shattered on September 22, 1993, when a plane carrying over 110 people from Tbilisi was shot down while landing in Babushera airport in Sokhumi. Around 20 people are known to have survived, but they did not include Bella’s two sons – Zurab and Temur – and her twin brothers – Vasili and Nukri – who were on board.

She last saw Zurab and Temur a few hours before boarding on that plane.

“They came home on the early hours of the 22nd,” she sobs, pointing at a picture on the wall of four men in their 20s. “Zurab asked me to play the opening to Daisi (“Sunset” in Georgian, a famous opera by Zakaria Paliashvili) on the piano. We can’t, I told him, it is 4am. Besides, it is very mournful. Why do you want me to play it?”

Eventually, she gave in – but she has not played the piano since. When tragedy struck hours later, this family of nine women – the oldest of whom, Bella, was 46 at the time, the youngest merely 10 months – was left to assume the worst. They have spent two decades mourning their loved ones and longing for the chance to bury them. Only Zurab was clearly identified; there was no news about the others, and none of the bodies was ever returned to her. Twenty years on, Bella’s grief is as raw as if it had happened yesterday.

She is not alone. The four men are among the 2,000 people whom the International Red Cross Committee (ICRC) says are unaccounted for from the 13-month war in Abkhazia in 1992-1993. About 150 of them are Abkhazians, including the famous poet Taif Adzhba.

A memorial dedicated to those fallen in the war in Abkhazia in early 1990s lays in the centre of Park Slavy (Park of Glory) in the heart of Sokhumi. Created by the sculptor Amiran Adleiba, it features a stylized sword stuck into the ground. Photo: Monica Ellena

No Dividing Lines

Parents from both sides began to search for their missing relatives immediately after the conflict ended.

Mothers and fathers used their personal connections – friends, neighbors, and surviving soldiers – to gather information to track down their children. They visited prisons and hospitals, travelled to potential gravesites, often at considerable risk and financial burden, to rummage through clothes looking for details that could help identify their loved ones – a tag, the corner of a photo, a shoe.

Georgian and Abkhazian parents soon realized they had to cooperate. Two associations – Georgia’s Molodini (Expectation) and Abkhazia’s Mothers of Abkhazia for Peace and Social Justice – led the way.

“We agreed we had to trust each other,” explains Vladimir Doborjginidze, Molodini’s energetic 86-year old chairman. “We were not enemies, just parents, equals in our grief,” says the historian, whose only son was last seen in Sokhumi on September 27, 1993. “I lost Zurab but I can’t be angry at them [the Abkhazians].”

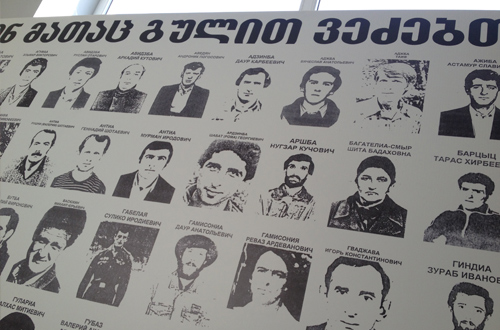

A banner in the Missing Persons Museum in Tbilisi lists the missing Abkhazians. Photo: Monica Ellena

Molodini has taken that message to heart. Inside the organization’s Missing Persons Museum in Tbilisi, the walls are covered by the personal belongings that parents shared to keep their memories alive – blurred black-and-white photos of young men smiling at the camera, boxing gloves, sport medals, diplomas, Soviet military cards from the Afghan war.

A big banner lists the missing Abkhazians, because “their parents are waiting as well,” explains Nineli Andriadze, Molodini’s deputy chairwoman and the museum’s caretaker, in her soft voice. She is still waiting to know the fate of her son Konstantin, whom she last saw on September 22, 1992.

In front of the museum is the Vashlijvari Fraternal Cemetery where some of the missing persons’ remains have been reburied over the years.

Eventually, the parents’ public diplomacy paid off, as over 314 people returned to Abkhazian and Georgian families over the years, recalls Vladimir.

That makes a huge difference. “In the Caucasus, visiting the grave is keeping the memory alive,” says Guli Kichba, who chairs Mothers of Abkhazia.

Turning the pages of “Hope Never Dies”, a book published by her organization that is full of faded photos of missing Abkhazians, she says: “If you light a candle, the soul will find peace.”

Guli knows this all too well. On the eve of St. Valentine’s Day this year, she was told that her son, Arzamet Tarba, had been identified. She had seen him last on March 14, 1993.

For twenty years she laid flowers in the courtyard of a green-painted house in Achadara, a village outside Sokhumi, where Abkhaz soldiers had told her that a few men, including possibly her son, were buried.

In fact, Arzamet was among the 64 bodies that Argentinean forensic scientists exhumed in Park Slavy (Park of Glory), in Sokhumi, last summer in an ICRC-led operation. A specialized laboratory in Zagreb, Croatia, is comparing DNA samples from the remains with the DNA of the missing persons’ relatives. So far 13 have been identified.

Humanitarian Dialogue

“The family of a missing person faces an ambiguous loss,” explains Jelena Milosevic-Lepotic, ICRC regional coordinator on the issue of missing persons. “There is no body, no physical proof of the death. They live in limbo, moving between hope their beloved might come back and despair that they might not.”

Families end up waiting, feeling like nothing is happening and that nobody is helping. In the aftermath of the war, psychological support and counseling for the families was not a priority in both sides.

Vashlijvari Fraternal Cemetery outside the Missing Persons Museum in Tbilisi. 44 missing persons’ remains have been reburied over the years on this cemetery; 23 of them remain unidentified. Photo: George Gogua

The parents’ associations eventually managed to get the authorities involved and both Sokhumi and Tbilisi set up State Commission on the Missing. The last meeting among parents happened in 2003 in Ochamchire, breakaway Abkhazia.

Thanks to the parenting network, a few exchanges still happened, including also the living. In one example, in 2006, the missing people were still alive: two girls on the Abkhaz list who got lost in the war chaos, were tracked down in Khoni, western Georgia, living with their Georgian relatives and reunited with their Abkhaz mother.

Politics eventually got in the way, the meetings stopped, and the dialogue faded.

The 2008 conflict revived the urgency of tracking down the missing. As ICRC set up a mechanism to search for missing people between Georgia and South Ossetia, Tbilisi and Sokhumi approached ICRC to act as a mediator.

That led to a coordination mechanism being set up in 2010. Under ICRC’s auspices, participants from Sokhumi and Tbilisi meet once a year to exchange information that could shed light on the fate of missing persons. That includes collection of detailed ante-mortem data, as even the smallest clue can be vital. It also includes biological reference samples for DNA analysis, and information about grave-sites – how the bodies were buried, their conditions, names of any witnesses of the death or the burial.

A major challenge is tracking down the family members, since people, especially those displaced from Abkhazia, have moved over the last twenty years, sometimes several times.

“The real break-through was that both sides decided to work together,” stresses Djordje Drndarski, who heads up ICRC in Abkhazia. “The Abkhazians asked to start with the exhumation in Park Slavy, and the Georgians asked for Babushera airport. Both were good projects to start with as they are precise sites, and the process proved to be a good learning curve.”

“The mechanism is a purely humanitarian forum, and participants try to safeguard it from politics,” adds Milosevic-Lepotic.

This is a point on which everybody agrees.

“The only purpose of this format is to help Georgians and Abkhazians to clarify the fate of missing persons,” highlights Nino Chavchavadze, Deputy Minister of Refugees and Accommodation (MRA), which is leading the process for Tbilisi.

Viacheslav Chirikba, the Foreign Minister of breakaway Abkhazia, echoes her words, adding that the program “is giving justice to the victims of the war, and we are ready to collaborate fully.”

Alongside the ICRC-led process, in 2013 two bodies were returned to their Georgian families “as a result of mutual benevolence,” says Chavchavadze.

The exhumation of 64 bodies took place in Park Slavy in Sokhumi in summer 2013. To date, 13 have been identified. Some families decided to rebury their beloved by the memorial. Photo: Monica Ellena

A light at the End of the Tunnel

That approach is yielding progress. As the identification process is underway for Park Slavy, the mechanism is now proceeding with Babushera.

To date, 58 bodies have been transferred from the grave site(the last transfer happened in 2002), 14 of which have been reburied by the families. 44 lie in the Vashlijvari Cemetery, but 23 of them remain unidentified.

Argentinean forensic scientists will arrive in Georgia in late spring to exhume the rest of them and support the identification process. They will also try to identify the remaining 35 bodies from Babushera. According to Chavchavadze, the transfer of the remains to Tbilisi will happen over time, starting in May.

For Bella, this may be good news. She has been wearing black mourning clothes for twenty years. “Now my boys are finally coming home,” she says. “I promised my grand-daughter I’ll wear a different color on her wedding day.”

Monica Ellena is a Tbilisi-based freelance journalist. This article originally appeared in Civil.ge in April 2014