The Devil’s Whip – scathing eye of the first Republic of Georgia

Tamara Svanidze, associate member of INALCO Center for Research of Europe and Eurasia, presents the way in which the Georgian satire digested international news and perceived country’s relations with its neighbors, as well as the role of the various European actors who intervened in the region during this key period of change in international affairs.

The present text was presented at a symposium dedicated to the centennial of the independence of the three Caucasian States (1918-1921), organized by EHESS and INALCO in June 2018 and entitled, “Exiting the empire, entering the International scene”. The article looks into representations of the outside world during the first Republic of Georgia (1918-1921), through the articles and illustrations that appeared in the famous Georgian satirical magazine The Devil’s Whip. The issues of this magazines form a part of the Georgian Collections of BULAC thanks to the donation of Mrs. Tamar Sharashidze.

In the 1900s, what is now called the South Caucasus has been a southern region of the Russian Empire, with Tiflis, currently Tbilisi, as the seat of the Russian Viceroy and its administrative capital. From the second half of the nineteenth century, this multi-ethnic and multi-confessional area, coveted by the bordering great powers, was in full journalistic, literary, but also political and military effervescence.

It is in this context, that the satirical press was born. In 1906, in Tifilis, the first satirical sheet of the Muslim East, Mullah Nasr-ad-Din and the Armenian satirical weekly Khatabala saw the light. The following year, the satirical Georgian magazine The Devil’s Whip was born. These publications, the pioneers of their genre in the region, still remain admired as the points of reference, both in terms of their creativity and for the freedom of expression they had shown in a particularly difficult context.

During 1909-1917, the Imperial censorship has been particularly rigorous, so these satirical sheets were published only sporadically. The Devil’s Whip ceased publication in 1908, only to be revived in 1915. This time, it ran unimpeded until 1917. After a brief interlude, during which Russia saw the end of its Empire, hopes of the democratic order and the Bolshevik Revolution, the sheet came back to life in December 1919, in a totally new political context. In the meantime, Georgia had declared its independence, which it would retain until 1921.

The images and satirical articles that are referenced in this article were published from December 1919 to January 1921, when Georgia’s short Republican experience came to a tragic end.

Satire in a collapsing world

It is not surprising that this period in history has given rise to such a publication, given profusion of political and military events both regionally and internationally, all condensed in a brief period of time. The number of satirical items that have appeared in the magazine regarding Georgia’s foreign policy is considerable, and the small selection covered here cannot pretend to do justice to the richness of the positions of these caricatures and these texts.

The Devil’s Whip has touched, among other issues, upon the arcane details of international politics, often thoroughly and always relating them to the readers. At the time, the maze of international politics was so complex that in addition to their calling to amuse and entertain, the caricatures also took on a rather important function of informing and educating the public.

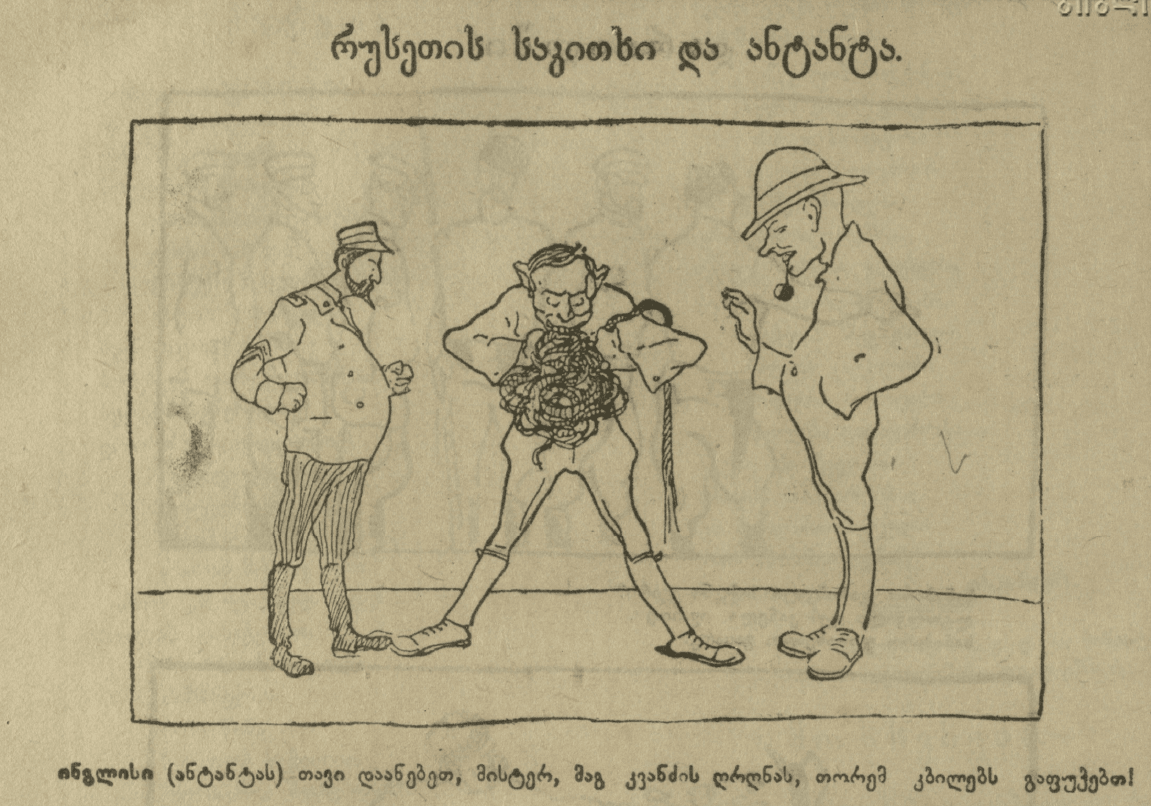

Several cartoons refer directly to the complexity of the international scene as their main theme.

In this sketch, entitled “The Russian question and the Entente”, the Entente incarnated by the central character, who tries in vain to unravel the tangled skein of the Russian political situation. An Englishman then advises him to abandon the task at the risk of breaking his teeth.

For The Devil’s Whip, satire is not rendered only through mockery or ridicule, it is used to level quite virulent political accusations. Still, we can only wonder about the extent to which these political statements reflected the actual political engagement of the editors and artists. Most of The Devil’s Whip material is signed with pseudonyms, so further, in-depth biographical investigations would be needed to uncover the personal stories of the many writers and artists.

The men behind the Devil

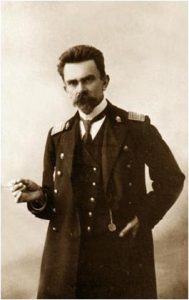

Still, we know two personalities, who had played a special place in the existence of this newspaper: Oskar Schmerling and Shalva Sharashidze.

Oskar Schmerling was born and raised in Tiflis, in a family of German immigrants who settled in the Caucasus in the early 19th century. He studied in St. Petersburg, and then in Munich before returning to work in his hometown.

His caricatures, many of which now form a part of the Georgian cultural heritage, sketch the picturesque scenes of daily life of the peoples of the

South Caucasus. He was not very profuse in the period that we focus on, yet, his rare drawings of 1920 stand out by their neat execution and the true artistic quality, when compared to sketches of his colleagues.

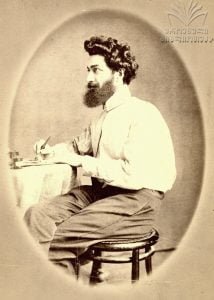

Shalva Sharashidze, was one of the founders and editors of The Devil’s Whip, for which he wrote many satirical articles and pamphlets under the pen-name Taguna (Little Mouse) . Sharashidze came from a politically engaged family – his two sisters and his brother represented the Social Democratic Party in the Constituent Assembly of the First Republic.

Finally, even if we do not know the identity of most of the collaborators or their personal stories, the very act of caricature or satirical speech undeniably show their commitment. While being independent of any party affiliation and despite denouncing the bureaucracy and corruption that affected the state institutions, a brief glance at some of the selected drawings allows us to conclude that the magazine’s positions were closest to the Social Democratic Party.

Characters: The Bolsheviks

The Soviet Russia, menacing Georgia physically and Social Democrats ideologically, is the main subject of The Devil’s Whip drawings, and its treatment is often dark and violent.

This drawing presents a Bolshevik satisfied with his work. The foreground is drenched in blood on which lay inanimate bodies, and the bubble reads: “I have done my duty by establishing equality and peace. No protest is heard. Everyone seems to be happy.” The drawing is captioned with a Latin phrase: “I have done what I could; let those who can do better”.

Like in this image, the caricatures in the magazine are always associated with a title, or sometimes a caption. When it speaks about the Bolshevik Russia, the text often comes in complete contradiction with the drawing, enunciating a truth that is radically opposed to what is shown.

In this type of caricature, the text is often taken straight from the Bolshevik leaders’ official declarations. Since the Bolshevik government is seen as broadcasting biased information, which is always positive and out of sync with the reality, the drawing aims to debunk the propaganda, show that the reality differs from these statements dramatically, by being more brutal and clearly unfavorable to the Bolsheviks.

In a series of drawings on freedom of expression in Soviet Russia, an anonymous cartoonist extensively uses this approach, citing extracts from official statements in its captions, which paint an enviable life that artists living under the Bolshevik regime supposedly enjoy. However, the drawings show that the reality is different.

Each ideal declaration is thus contrasted by a visual denunciation of the Bolshevik cruelty. The image openly contradicts the text, but in return, the absurdity of the text makes the image all the more poignant, more violent.

Illustrations that appear in these series condemn the violence and terror of the Bolsheviks, but also portray the prevailing backwardness and misery, for which the Bolsheviks are held solely responsible. These condemnations lead the authors to paint a contrasting image of more democratic, more prosperous and civilized Georgia.

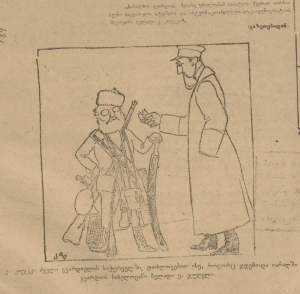

Many cartoons could be cited to illustrate this approach, but the series below entitled “Communists visit Tbilisi” are perhaps the most eloquent.

Here, we see the Russian Bolsheviks walking around the Georgian capital, struck in awe at the sight of running water, the shelves of shops filled with tobacco and foodstuffs or looking up at the lit electric streetlights. The author turns upside down the cultural representation of the Caucasus as an exotic, primitive and cruel “orient”, which dates back from the era of the Russian romanticism, and depicts the Bolshevik Russia immersed into barbarity and destitution, while simultaneously highlighting the achievements of the young Georgian Republic in social, educational and agrarian reforms.

Characters: the enemies

Cartoons about the international context are populated by characters either inspired by reality or completely fictional, built around distinctive visual signs.

Thus, the key Bolshevik leaders, brought to a center-stage of this satirical publication as bearing responsibility for the decay of Soviet Russia, are caricatured – they bear ridiculous traits, deformations, or even present the traits of animals, hinting at their true nature.

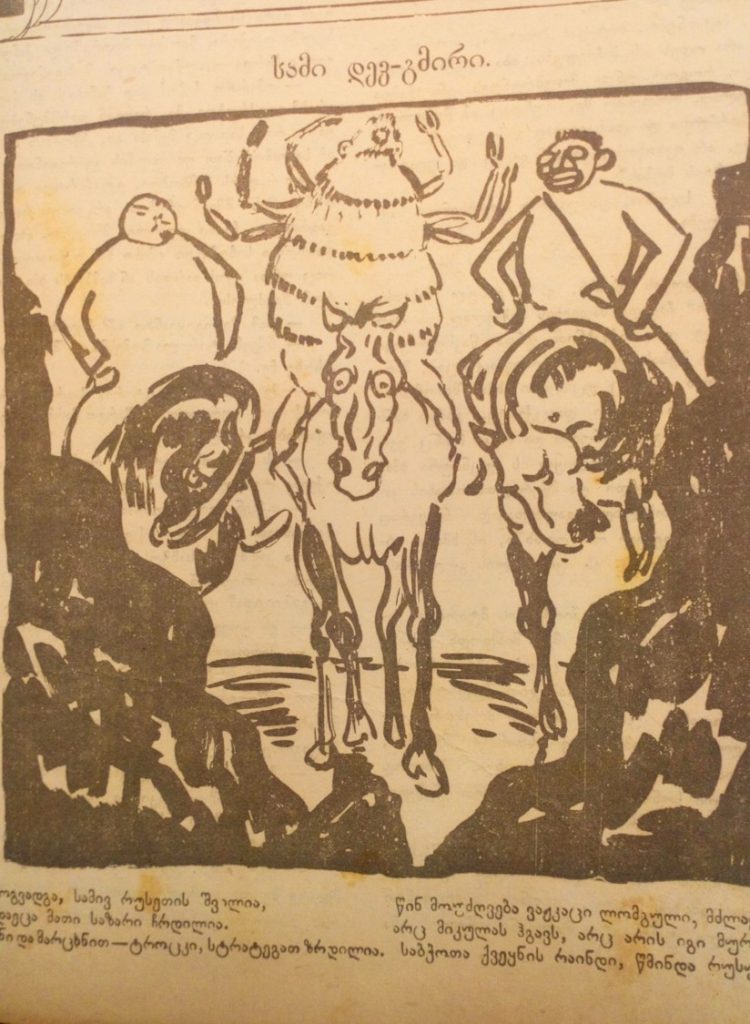

Thus in the drawing above, Trotsky (right) is depicted with unkempt hair and googly eyes that give him the appearance of a madman. When it comes to Lenin (left), the caricaturists focus on his smooth face and slanted eyes, making him the epitome of Asian despotism. These two characters are systematically represented in the company of a giant louse, a symbol of Bolshevism that can only inspire contempt and disgust. By reading the short humorous poem that accompanies this caricature, we understand that Trotsky, Lenin and the Louse are intended as a satirical imitation of the famous painting of V. Vasnetsov “The Three Bogatyrs”, mythical heroes of Russian fairy-tales.

The Bolsheviks are not the only Russian targets of the Devil’s whip: General Denikin, their “white”, Tsarist enemy, but also a formidable threat to Georgia’s north-western border, is also frequently caricatured. Though in contrast with barbaric Bolsheviks, Denikin’s caricature is targeting his troops decadence and debauchery. In particular, his efforts to coax the people of the Caucasus to rally under his banner are ridiculed.

The magazine also points an accusatory finger at the internal enemy: the Georgian Bolsheviks of the are seen threatening the beautiful edifice of the Georgian democracy.

The caption of this caricature refers to the restoration of the legal status of the Georgian Communist Party, previously banned, but recognized by the government in May 1920. The Bolsheviks, literally undermining the building, tell the government: “You can do your job as much as you want. For us, our legal situation is a joke. If necessary, we can dig in tracks blow the bombshells from the underground.” The Devil continues to assign this sarcastic tone to the Bolsheviks, as Georgia finds itself encircled by them, up until the moment when the caricatures take a much more dramatic and alarmist turn, as the Soviets start to present an existential threat to sovereign Georgia.

Pest on both your houses: Ankara and Moscow

During the historical period that we address, relations between Ankara and Moscow have developed into a veritable “Ankara-Moscow axis”, threatening Georgia with hostile encirclement and eventual dismemberment.

The Devil’s Whip is thus particularly virulent in its portrayal of Turkish officials, shown to be as bloodthirsty as the Bolsheviks are. Many cartoons illustrate this Turkish-Soviet rapprochement by presenting it as a fully natural development, given the oppressive nature of two regimes, and are thus mobilizing the readers’ opposition to both.

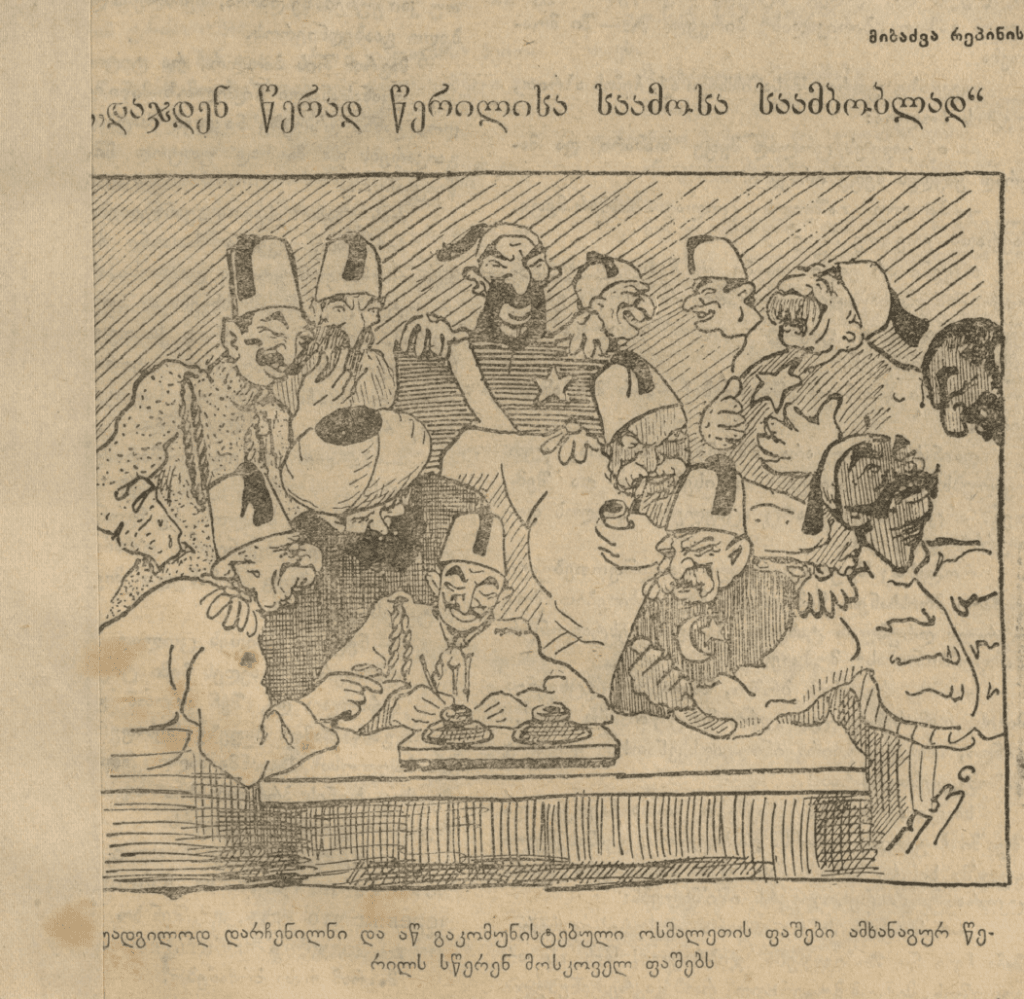

Similarly, the Congress of the Oriental Peoples held in Baku is presented as a cynical masquerade and concentrates all the venom of Georgian satirists. An October issue features a striking caricature, imitating a famous painting of I. Repin. This is a pastiche of the famous “Zaporozhian Cossacks writing a letter to the Sultan of Turkey”, painted in the 1880s, where Repin was able to convincingly portray the intense pleasure that the Cossacks experienced in writing their insulting missive.

There, by ironic turn of the tables, the protagonists are captioned as “Tatar Pashas who became communists and – having lost their patrimony – are sending a friendly letter to the pashas of Moscow”.

South Caucasian neighbors

It is also interesting to observe through these humorous publications how Georgians perceived their immediate neighbors. This, first of all, comes through a vision of Georgia in the neighborhood. Notably, the characters embodying Georgia often appear as providential men who strive to establish friendly relations between the Caucasian neighbors and to appease national conflicts by multiplying the organization of peace conferences. The Devil’s Whip has even published a series of caricatures entitled “Perpetuum mobile”, to ironically signify that these intentions have been reproduced in vain since the beginning of time.

But every crisis between the Caucasian neighbors brings to the forefront stereotypes rooted in the traditional imagination. Thus, some of magazine’s caricatures re-engage the dominant national stereotypes in telling their story.

The drawing below is an extension of the rivalry that in the nineteenth century had already nourished sharp controversies between Armenians and Georgians, each nation contesting their “historical rights” to certain territories.

This front-page caricature refers to the news of May 7, 1920, the moment of the signing of the Russian-Georgian friendship and neutrality agreement, which was disputed by the Armenian government on the basis that it did not provide for the attachment of certain districts (Borchalo and Akhalkalaki and part of the province of Batumi) to Armenia.

Here we see Noah, whom the Biblical tradition sees reaching land in the mountains close to the region, sitting on Mount Ararat, complaining of the excessive appetite of his child, symbolizing Armenia, which he tries to restrain and which, according to him, “Wants to claim everything he sees, saying “it’s mine! it’s mine!” The image evokes the most delicate and thorny question of the time: that of the borders between the Transcaucasian nations, which was a source of many disputes, and even of armed conflicts.

Yet, when The Devil’s Whip speaks of Armenia, the predominant image is that of a victim of Turkish abuses, as well as of the West – which is portrayed as indifferent and inactive despite statements in Armenia’s favor.

The draftsman uses irony by titling the cartoon of the month of May “The Armenian Mandate”.

In a set stage, drawn from the famous Georgian opera Abesalom and Eteri, Armenia is embodied by the young maid Eteri, kneeling in a posture of despair. The Englishman, the Frenchman, and the Italian depart, refusing to take her under their protection, abandoning her to the satisfied Turk who had claimed her. The reference to the Georgian opera is immediately understood by the readers, who are invited to equate Armenia with the strong image of an innocent and ignominiously deceived victim of a plot, hatched by the traitors. Here, the roles are clearly defined, the denunciation of the West is radical and unequivocal.

As for Azerbaijan, it is pilloried by The Devil’s Whip for its alleged deceit and treason. This March 8 image ironically bears the title of an old Georgian saying, the equivalent in French of “It is in true need that one recognizes his true friends”.

It shows Georgia perched on a stool, in an unstable position, trying to open the lock and access Batumi, a city then occupied by the British, while Azerbaijan is sawing one foot of the stool, uttering the following words: “It pains me to seeing my dear neighbor perched so high… I am afraid he will hurt himself. I’m going to shorten the stool, so he comes down easily. But I have to hurry, so that he does not have time to open that door.” This caricature refers to Azerbaijan’s hostility towards the reunification of Batumi with Georgia. Azerbaijan undermining Georgia’s work refers to the alleged support that country had rendered to the political grouping Seday Milet (The Voice of the People) in Adjara, which promoted pan-Turkic ideas.

Again, the transformation of the neighbors had forced the magazine to reassess Georgia’s posture. The forced Sovietization of two neighboring countries had reinforced in The Devil’s Whip the image of Georgia as an oasis of peace, the fortress of justice and order, as suggested by this representation “Refuge of the conquered” and whose legend says that “All paths now lead to Georgia!”

Europe

The satire of The Devil’s Whip also informs us of the Georgians’ perception of Europe, shaped by political reality of the day, but also representing a projection of the readers’ collective consciousness.

At the beginning of the year 1919, Georgia sent a delegation to Europe under the leadership of Karlo Chkheidze, which included one of the Socialist party luminaries, Irakli Tsereteli. Their mission was to obtain legal recognition of the new state. The delegation took part in Versailles Conference and for two years undertook a significant effort to foment the European public opinion in favor Georgia.

One of the first issues of The Devil’s Whip of December 1919 shows us Chkheidze and Tsereteli in front of an enigmatic and silent Sphinx, representing Europe. The two men wonder, if the sphinx would deign to utter a word one day.

Thus, The Devil’s Whip portrays Europe as a mythical deity full of wisdom, power and prudence, unmoved by the patient effort of the two Georgian politicians. Indeed, suggests the caricature, who would dare to meet the challenge of recognizing the countries of the Caucasus?

In the same vein, The Devil’s Whip throws, still in December 1919, a disenchanted look at the Paris Peace Conference, showing it infested by mold and cobwebs, portraying the lethargic state of carelessness, with which the Allies are examining the “Georgian question”. These drawings show not only the culpable indifference of Europe, still a source of the Georgian hopes, but also the clear-sighted disillusionment of the Georgians who, for want of anything better, had turned to it for aid.

In addition to seeking protection from the Entente, Georgia was also seeking the support of its friends of the Socialist Second International. In September 1920, The Devil’s Whip took a keen interest in the triumphant reception the Georgian government gave to the socialists Karl Kautsky, Ramsey McDonald, Huysmans and Renaudel.

The number of humorous, yet deeply sympathetic texts and images devoted to these personalities alone summarizes the importance given by The Devil’s Whip to their visit. The details of their movements are narrated in the form of a soa p opera and the smallest of their speeches is relayed in the pages of the magazine.

p opera and the smallest of their speeches is relayed in the pages of the magazine.

For example, the paper publishes this drawing by Kautsky wearing the old costume of the Georgian national guard, as well as a feuilleton entitled “Look, Kautsky”, in which a peasant from the ardently socialist region of Guria retells – in a truculent dialect – his encounter with the German Social-Democrat, a meeting he would not have even dreamed of in his young age, when he imbibed the ideas of socialism by reading excerpts from Kautski’s works.

These sets show another aspect of the newspaper: its benevolent gaze at the few individuals it considers important for Georgia and its poised look at Georgians who, ideally, had embraced social democracy.

The visions of Georgia

The Devils Whip most often represents Georgia a young, but formidable maid, who does not allow herself to be intimidated by a white bear (Denikin) roaming alongside her, nor by a formidable adversary in the game of chess, representing here Cooke-Collis, British general and governor of Batumi.

The metaphor of the chessboard of regional diplomacy is not surprising, since Batumi is very much at the heart of international disputes at this time. Georgia appears in this cartoon as a skillful strategist, she inflicts the check-mate on Cooke-Collis. This drawing of the month of April echoes the British General’s ultimatum to the First Republic to withdraw its armed forces from the region.

Indeed, the city of Batumi was occupied by the British between December 1918 and July 1920. This strategic – from the point of view of the British Crown – occupation had irked the Georgians, who claimed the city as an integral part of their country.

In February 1920, following the Bolshevik advances in southern Russia and the unrest that escalated in the city, the British-backed Batumi government made the decision to withdraw. Incidents between the British and the Georgians over the control of the railway have multiplied, as the Georgian troops advanced on the region.

The British High Commissioner in Tiflis, Oliver Wardrop had played an important role in resolving these tensions. Despite the latter’s effort to keep the British troops in Batumi, which he saw as a way to guarantee Georgia’s security, the Crown forces withdrew and the region was ceded to the Georgians in summer 1920.

Since the end of the 19th century, the Georgian press has been presenting Oliver Wardrop with almost unconditional admiration: he was perceived as Georgia’s true friend and the defender of Georgian interests in Europe. However, the events around Batumi have led the Georgians to develop certain defiance and mistrust towards his character, so the magazine treats with suspicion his declared good intentions.

The Devil’s Whip denounces Wardrop’s double speak and his double allegiance.

This caricature shows the British commissioner in the guise of devious Orpheus, reflects this feeling. Indeed, by his deceptive song, Wardrop-Orpheus tries to lull the Georgians into forgetting Batumi by reminding them opportunely – as he was the translator of this classical Georgian poem into English – of the aphorism by Shota Rustaveli “What you give, is yours, what you hold – is lost”.

Along the same lines, one finds in the drawing (left) the criticism of the perfidious speech of the Entente, presented in the guise of a butcher who mutilates a leg of the prostrate Georgia, its face marked with stupor. In doing so, the butcher reassures Georgia by saying he acts for his ultimate good. This caricature echoes the Entente-backed project of proclaiming Batumi as a free port under the mandate of the League of Nations. This is interpreted by Georgians as an amputation of their country, as the caption also indicates.

Along the same lines, one finds in the drawing (left) the criticism of the perfidious speech of the Entente, presented in the guise of a butcher who mutilates a leg of the prostrate Georgia, its face marked with stupor. In doing so, the butcher reassures Georgia by saying he acts for his ultimate good. This caricature echoes the Entente-backed project of proclaiming Batumi as a free port under the mandate of the League of Nations. This is interpreted by Georgians as an amputation of their country, as the caption also indicates.

The departure of the British troops, gives the Devil’s artist an opportunity to imagine a long dialogue between two rats – “speculators” (as the traders in the black market were known) – of Batumi. Disillusioned by the new Georgian government, which no longer leaves them free to pursue their fraudulent ways, they decide to migrate to Soviet Russia, which they imagine as a real “socialist paradise”, a hotbed of speculation and clandestine trade, where leftovers are abundant.

While the military operations and international problems mobilized all energies during the First Republic of Georgia, they hindered the progress of the major domestic projects.

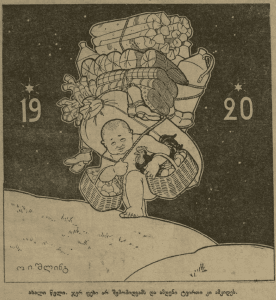

This is what The Devil’s Whip of January 1920 illustrated with a somber cartoon signed by Schmerling: the New Year 1920 is personified by a baby, weighted down by a heavy burden of the economic and social challenges.

This is what The Devil’s Whip of January 1920 illustrated with a somber cartoon signed by Schmerling: the New Year 1920 is personified by a baby, weighted down by a heavy burden of the economic and social challenges.

In conclusion

The satire of The Devil’s Whip has been willfully anchored in a complex reality of the time, which it described in a dedicated and engaged fashion, thus giving us an intimate glimpse into the Georgian society of the day and the politics of the First Republic, but also of the way the Georgians perceived themselves, their neighbors and international politics at the time.

This satirical magazine had set as its objective to play an ambitious role of an observer, monitoring the military and diplomatic news, and transforming the literary and visual culture into a critical political “weapon”, while drawing on its intellectual complicity with its readership. In a pioneering move for Georgia, The Devil’s Whip mixed popular means of expression (caricature drawings) with elitist references, advancing its message in protection of the Democratic Republic a civic-minded, committed and politically militant fashion.