“Democracy with Social Inertia” – How the Republic Built Schools

“The primary education is universal, free and compulsory. Public schools system is envisaged as one organic whole, where the primary school represents the foundation for secondary and higher schooling. Instruction at all levels is secular”… “A school established on private initiative is subject to the general public education law.”

The Constitution of the Georgian Democratic Republic adopted in 1921, Chapter 12, Education and School.

by Irakli Iremadze

The Georgian Democratic Republic existed for mere 1028 days, and most of this time was engaged in fighting. It is only to be expected that the lion’s share of the expenditures (approximately 30-40%) were dedicated to defense. Still, in 1919-20 the Ministry of National Education received 7% of the total national budget.

This attention to education was in part explained by personal background of the officials, many of whom were teachers themselves, but it drew strongly on their party ideology, and formed the key characteristic of their progressive political vision.

Teachers for progress

When writing about the first generation of the Georgian Social Democrats, publicist Giorgi Tsereteli remarked:

“they are village teachers, intellectually advanced seminarists [students of the religious school] and graduates of the Pedagogical Institute, which have set themselves an objective to teach the uneducated people how to read and write, to acquaint them with the clear and argumentative views of scientists and to teach them how to follow the world developments.”

Several representatives of this generation – known in Georgia as “mesame dasi” – “The Third Alliance” – were often the enlightenment figures, especially in western Georgia, which was to become a true cradle of the Georgian Social-Democracy.

Isidore Ramishvili, graduate of the Tbilisi Religious Seminary, has established a school in 1880-90s in his native province of Guria and has founded the Gurian Popular Library. Later on, Social Democrats have created workers’ reading clubs in industrial districts, organized Public Universities, open to all who wished to attend, in Tbilisi as well as in Georgia’s provinces.

Thus, twenty years ahead of Georgia’s actual political independence, these teachers were laying the foundations – and testing approaches – to modern education system, while being politically active.

Following the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, Georgia’s political forces have convened the First National Assembly of Georgia, where the National Council, the embryonic representative body, was elected. It would fall to this very body to declare Georgia’s independence on May 26, 1918.

There were many teachers in Georgia’s leadership at the time, both in the government and in the legislature, and this trend was sustained throughout the short life of the First Republic. 18% of the delegates elected to the Constituent Assembly in 1919, were teachers.

It came as no surprise, then, that even as Georgia’s political future remained unclear in 1917, the National Council was already drawing up the education policy.

From the start, Commission on Schooling and Arts was created, which actively took to reorganizing Georgia’s schools. After the independence was declared, the Commission’s mandate was gradually expanded and its scope more clearly defined, until it has finally emerged as the “Commission on Public Education”. The Ministry for Public Education was its counterpart in the Government, which was tasked to submit specific proposals for fundamental reform of the education system.

The portfolio of the Minister of Public Education went to the leader of opposition Social-Federalists, Giorgi Laskhishvili. However, the true father of Georgia’s education reform was his deputy, Social Democrat Noe Tsintsadze. Not surprisingly – himself a teacher.

From the Empire to the Republic

Collapse of the Russian Empire was truly a political and institutional earthquake. Establishing the new, Democratic Republic in Georgia was a daunting task. It fell to the Social Democrats – the first time this political force, though rising in prestige across Europe, actually came to power.

From its first days, the Georgian Democratic Republic had to build its institutions from the ground up. Certainly, the political system of the republic did not exist before. But transforming the education system on democratic principles was among the government’s topmost priorities.

In the Russian Empire, the majority of Georgia’s population had no access to education. The legendary “Society for Spreading Literacy among Georgians” – the first 19th century enlightenment movement led by young aristocrats, which soon gained massive public following and made significant impact – has managed to improve literacy rates. However, the schooling – especially secular, and in Georgian language – remained accessible to only a small strata of the population.

Apart from the problem of accessibility, the Russian imperial system of education was ideologically incompatible with the new democracy. The circular letter sent by the Ministry of Public Education to the school principals, sent out in 1918 reads:

“As we abolish the system based on inequality, our system of education must change fundamentally. All obstacles impeding the primary school students from continuing their education in higher grades must be removed, so that our school becomes socially integrated.”

Dire legacy

The existing state of education system required urgent action. To begin with, the number of schools was grossly insufficient: in 1914, a total of 864 schools were functioning in Georgia. By 1917, this number did not significantly change.

With reform proposals still on the drawing board, the government wasted no time to begin transforming religious and civil schools into public schools, while also taking on the costs for the upkeep of infrastructure and remuneration of teachers and personnel.

Apart from the sheer lack of schools, the distribution of the existing school facilities was also very uneven. Most of them were in larger cities and in several districts (Ozurgeti, Shorapani, Kutaisi).

According to the 1914 data – the most recent available by 1917 – there were 80 thousand pupils enrolled in those schools. Since there was no precise census data available, the Public Education Commission roughly estimated that there were more than 200 thousand children eligible for schooling.

Those pupils who were enrolled, lacked books, especially in Georgian. Under the Russian Empire, classes were mostly taught in Russian, with only very few schoolbooks published or translated into Georgian.

Adding to that was the dearth of qualified teachers. While several teachers’ training schools existed, they lacked both expertise and the scale to train a sufficient number of teachers, especially in specialized subjects, such as natural sciences.

First measures

With its challenges daunting, the government got promptly to work. Still in summer 1918 – barely two months after the declaration of independence – the Ministry has approved the list of subjects for the combined, 8-year primary and secondary schools (gymnasiums). The following subjects were included: Georgian, Russian, German, French and English languages, philosophy, law, calculus, geometry, algebra, trigonometry, physics, history of Georgia, history of the world, geography, natural sciences, drawing and singing.

Simultaneously, a special re-training summer school was held for the secondary school teachers, with lectures led by the luminaries of the Georgian science at the time – and for many decades to come – among them: Ivane Javakhishvili, Dimiti Uznadze, Ioseb Kipshidze, Giorgi Akhvlediani, Alexander Javakhishvili, and Noe Kipiani.

These efforts bore fruit – the 1918 school year saw most schools switching to Georgian as the primary language of instruction. Minorities could benefit from instruction in their native languages – schools were operating in Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Russian.

Another ideologically and practically important change was made in November, 1918. Teaching of the Holy Scripture, one of the mainstays of the Imperial education system, was abolished through the law initiated by Leo Natadze, head of the Commission on Public Education, and passed by the National Council on 26 November.

Those parents who wished their children to continue religious education, could do so through private funding, while the government was offering the use of the school premises, after the completion of the regular classes.

The decision – attacked by opposition National Democrats and also controversial publicly – was, nonetheless, carried through. Interestingly, in practice, religious education classes continued to be taught to Muslim students, in the areas where they represented the majority of the population.

Towards the new system

It took almost a year to prepare the framework for the education reform. Both the government and the parliament agreed, that aside from the purely financial constraints, training of the sufficient number of teachers to an acceptable level represented the biggest challenge for expanding Georgians’ access to education. To address this matter, a special law was passed in 1919, establishing the state-funded vocational training and re-training courses for the teachers. These could train the batches of 250 teachers at a time, with each group trained for two months.

Additionally, the teachers’ training schools and the Tbilisi Pedagogical Institute were subordinated to the Ministry of Education, the curricula was revised, standardized and widened.

The teachers were in short supply, especially as the government was boosting a number of schools fast. But as the body of teachers expanded, their precarious financial state became obvious. The archives of the Ministry of Public Education bear witness to numerous appeals for financial help. The newspapers published articles about teachers living in precocity.

Beset with inflation and economic crisis, the government found it hard to pay adequate salaries. The Constituent Assembly has voted several times – at the initiative of female MP and teacher herself, Christine Sharashidze – to increase teachers’ salaries and to provide bonuses to catch up with the inflation, but these steps have failed to significantly alleviate the problem.

Making education compulsory also put the pressure on the government to assure attendance of those pupils that were living in poverty. Families wrote to the Ministry, asking for clothes and other necessary items for their children.

The government decided to cover the expenses of those pupils that lived in extreme poverty, and of the orphans. Social-Democrats have obviously considered such assistance being one of the primary duties of the Republic.

The Constitution, passed days before the capital succumbed to Soviet intervention in 1921, read:

“The State considers it as its objective, to provide all children, living in poverty, with nourishment, clothing and school items during their primary education. The State as well as local self-government bodies shall annually allocate a portion of their respective revenues towards attaining this objective.”

„Democracy with social inertia”: the vision of reform

The document framing the key avenues of education reform was completed in summer 1919. Noe Tsintsadze, deputy Minister of Public Education was the true parent of this policy and, logically, it fell to him to present it on 17 July 1919 to the government.

His statement “On Reorganization of Secondary Education” said in its preamble

“Old school belongs profoundly to the old reality with both its general direction and its content and thus, evidently, it can not conform to our current life and to its objectives. It necessitates transformation, re-organization.”

So what was, in the government’s mind, the foundation of schooling that responded to this “new reality?

“Democracy with social inertia – this is the core foundation for the burgeoning of our new school; the development of human nature in all of its entirety and individuality, the development of its free will – this is the core objective which our school must serve!

We must note, that in a democratic state, built upon the idea of equality, it is impermissible that each strata of the society, whether defined socially or by title, has its own independent trajectory of development.

Equality is not only a matter of rights, it necessarily assumes cultural equality and, therefore, the vital forces of our society must exist in similar, equal and equitable conditions for their development. It is therefore evident, that we need a system of general education for all strata of society, unified with its content and [educational] program… We need one school, unified in its content and its composition.”

More specifically, the new reform foresaw creation of three-stage education system. The first one, so called “public school” was the elementary school; the secondary and tertiary stages lasted four academic years each. The initial plan was to have the secondary and tertiary stages based on unified curricula, while professional diversification was foreseen at a later stage, based on pupils’ decision.

Starting 1920, pupils could already continue their education in agrarian secondary schools, which was allowing for professional training in several areas of agriculture and agricultural engineering. These were subordinated to the Ministry of Agriculture, although their core curriculum was done in coordination with the Ministry of Public Education.

This orientation towards professional bifurcation of the pupils, individual follow-through based on individual needs – authors of the reforms admitted, that these policies were hard to put in practice, due to formidable economic challenges, the existing level of education, and the lack of qualified teachers – but they have set them as their objective nonetheless. The reform document discussed in some details the European schooling models, that were considered exemplary at the time.

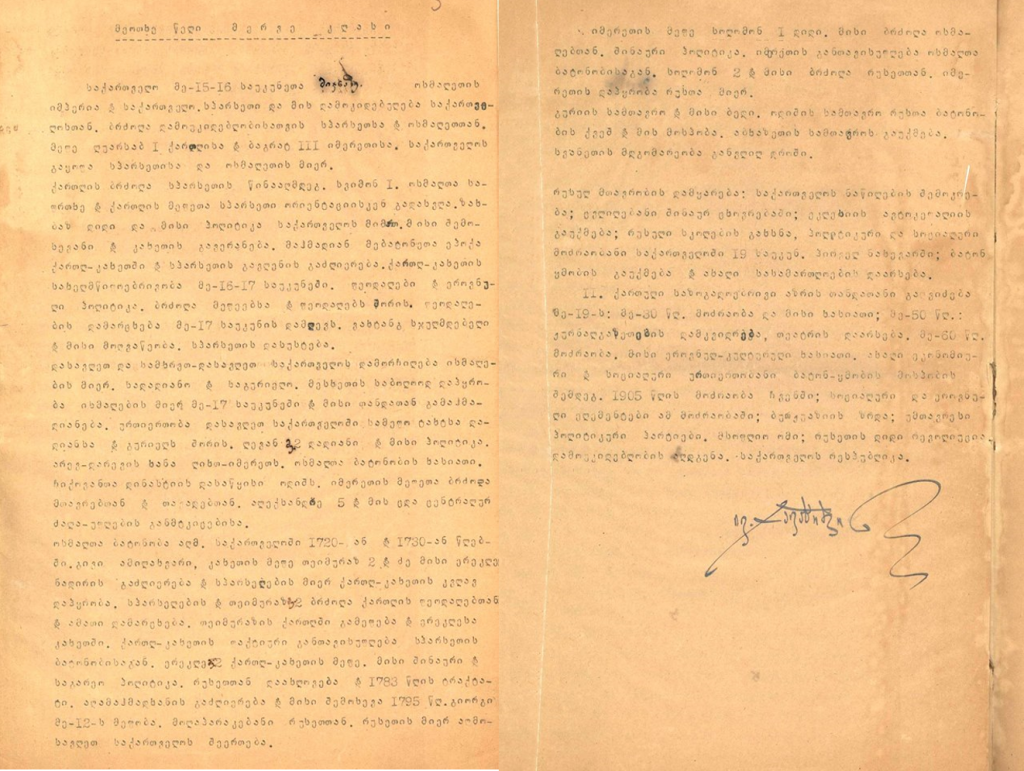

Curriculum of the History of Georgia for 8th graders, 1919-1921, signed by Ivane Javakhishvili, one of the founding fathers of Tbilisi State University.

The final version of the reform strategy was to span the period of 1919 to 1923, and the changes were to be implemented in several stages. The curriculum had to be adjusted accordingly.

Based on available resources and experience, it was decided to stop instruction in classical languages (Latin, ancient Greek). Instead, it was decided to expand the teaching of German, French and English languages. Natural sciences were to also be taught more profoundly. Psychology, political economy, logic and law were added to the curriculum and so were physical exercise and handiwork.

The policy document also dealt with the lack of textbooks, purporting to create the Education Committee to review, evaluate and license textbooks. By school year 1920-1921 most of the textbooks were already available in Georgian – part written by the Georgian authors anew, part translated. The Ministry as well as the Union of Teachers were publishing periodicals dealing with the theoretical and practical aspects of instruction.

As the reform document was passed, it became the basis for the law “Decree on Secondary School Reorganization”, which stipulated – “All secondary schools of general education, supported by the public expense of the Republic of Georgia are of the same type”… “the aim of the secondary school of general education is to bring up the generation, give them completed secondary education while preparing them for a higher education institution.”

Special commission was created, tasked with implementing the reform, which was headed by the Dimitri Uznadze, Professor of the Tbilisi State University. The Ministry decided to adopt the Maria Montessori teaching method as a methodological basis for reform and planned to invite several of Montessori’s followers to train the Georgian teachers.

The local self-government reform was being implemented in parallel with the education reform, and the local governments were expected to play an increasing role both in management of the schools and in their financing.

Path, interrupted

Despite the challenges, the first results of the reform were impressive. By 1920, the number of schools reached 1924, which meant it expanded by by 123%, compared to 1914/17. The number of enrolled pupils has doubled, reaching 162 thousand.

The reform, striving to educate the citizens of democratic society, offering the opportunities for development to all, was never brought to a completion. As the troops of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic have ended the Georgian Democratic Republic, the secondary school system has become increasingly indoctrinated and totalitarian.

Many of the scientists, still young professionals as they drafted these reform proposals, would survive the initial cataclysm and lay foundations of the Soviet Georgia’s academia. Most would meet their end in the Stalinist purges of 1930s.

This post is also available in: ქართული