EDITORIAL: Karasin Slams on the Brakes

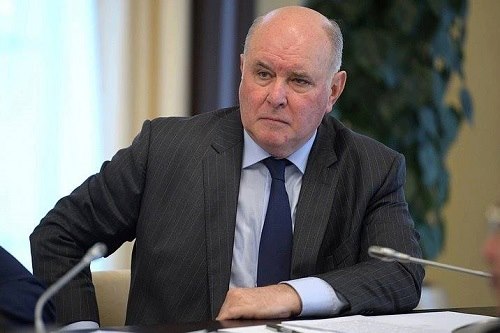

Grigory Karasin. Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia

… but Tbilisi should chart its course

Russia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Karasin is a man of very few smiles. But even by his own standards he has been positively glacial of late and that, just as Tbilisi was prepping for the overture. And even though the Smolenskaya Ploshchad’, as the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Stalinist tower is known, got to airing all the old bogeymen in bilateral relations, it is important for Georgia to keep focus on going forward.

Emboldened by lessening tensions and the growing trade with Russia, which has moved to the second place as country’s trade partner last year (trailing only Turkey), Tbilisi seemed willing to bring things with Russia up a notch. On December 20, Georgian diplomats have signed an agreement with the Swiss company SGS in Bern, opening the way for implementation of the 2011 customs agreement that would widen the passage of goods from Russia to Georgia and Moscow’s key South Caucasus ally – Armenia, by de-blocking the routes through occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Shortly afterwards, Prime Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili said the government was ready to upgrade the level of talks with Russia. The government is also mulling over “very interesting” initiatives to engage with Sokhumi (and, perhaps later, more recalcitrant Tskhinvali). This is the first time since 2008 that Tbilisi has considered to engage directly with its occupied provinces.

Karasin dashed the prospects of détente. To begin with, he did not show up to Bern to sign the Russian end of the deal with SGS – and that after years’-long complaints about Tbilisi undermining it. Instead, Russia asked for more time to thrash out “the details.”

This was followed by a strongly worded interview to Russia’s Kommersant daily, in which he suggested that by 2011 agreement Georgia has recognized that its customs space does not include Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Not only this assertion is legally imprecise, but this kind of talk undermines the chances of the Georgian government moving forward without losing face in the eyes of its public.

In the same interview, Karasin also disparaged his counterpart, Prime Minister’s Special Envoy Zurab Abashidze for being “duplicitous” in describing Russia’s position to the public and proceeded through the laundry list of the Russian demands – essentially saying no movement forward is possible unless Georgia recognizes the “facts of the ground” of the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

The Kremlin’s corridors are dark and full of fears these days – to paraphrase the Game of Thrones dictum – especially as Putin’s “elections” loom. This is not because their result is in doubt, but because by old Soviet tradition, the Tsar might use the opportunity for reshuffling his entourage. The Russian Foreign Ministry tower looks particularly shaky: its veteran leader Sergey Lavrov is about to retire, reportedly leaving the Smolenskaya Ploshchad’ a mere shadow of the Presidential Administration.

All of these are intriguing developments to keep an eye on. But when its occupied provinces are concerned, Tbilisi must not fall into an old trap of looking for “other Russia” more sympathetic to its plight. The Kremlin has asked repeatedly to take it at its word.

Georgia must care even less about whether Ambassador Karasin wants to look tough for the upcoming beauty pageant on Staraya Ploshchad’, where the Presidential administration sits. What is important, is to take the stock, keep the initiative and move forward.

The Georgian Dream has not yet articulated a comprehensive vision of what it wants to do about Georgia’s outstanding conflicts. Six years into governing, it is high time to do so. The 2018 presidential and 2020 parliamentary election cycles might be a good pretext to put a face on its new policy. The recent polls show these issues slipping off the public radar. And while one can see this as problematic, cooler heads might make for more receptive audience to new ideas.

Tbilisi’s response can be two-pronged – tangibly hardening the diplomatic stance on Russia, while continuing to signal an opening to Abkhazia and South Ossetia on practical, day-to-day issues. While it is too premature to speak with much less open Tskhinvali at this stage, Sokhumi could be a good starting point.

Some would say, that Sokhumi is bound to shoot any proposals down as well, especially given the tense political environment there. Others will argue, that even if it were the case, Russia would block any meaningful Abkhaz engagement. Both views are reasonable, and even likely. But official Tbilisi must keep in mind that its crucial objectives at this stage are to get its international partners act against the Russian intransigence, while convincing the Georgian voters that meaningful change is possible and realistic.