Dispatch | Feb. 6-12: …and the Trolley Rolls

Who’s pulling the lever for Saakashvili – Georgia’s ‘multitrack/drifting’ foreign policy – the punishable art of self-theft

Trolleys have long disappeared from the streets of Georgian cities. Still, philosophical problems associated with them remain. This week’s ethical dilemmas included how (and whether) to save jailed ex-President Mikheil Saakashvili, whether the country’s European future is more important than the financial troubles of its ruler, and whether art should stand above the law.

Here is Nini with this week’s Dispatch, trying to take over as philosophers fail to do their job correctly these days…

Who’s gonna pull the lever?

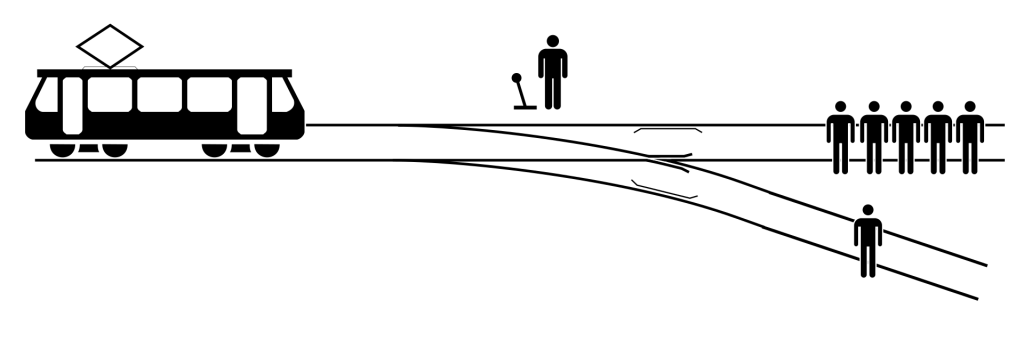

The trolley problem is a popular thought experiment about ethics. A person stands near a tram track to which five persons are firmly tied. The trolley is approaching to kill them, but the person can pull the lever to side-track the trolley to a track where only one person is tied down, thus killing one instead of five. While some would claim that one death is preferable to five, others see that intentions matter more than consequences and that pulling the lever ultimately means the murder of that one person who would otherwise live.

There is no shortage of similar ethical dilemmas in Georgian politics. Still, it became particularly relevant as many think ailing Mikheil Saakashvili, left in custody by the court, may die. Yet, everyone seems to disagree on who is tied to which track. Some see no dilemma. Some others deny that they are in a position to pull the lever.

The government definitely has the lever but continues to claim that the trolley is rolling in the right direction and that the body on the tracks is doing self-harm. The ruling Georgian Dream suggests that Saakashvili has voluntarily tied himself to the rails hoping to stop the trolley. His irresponsible behavior may now cause him to be run over. Now that Saakashvili senses the imminent danger, the government says, he wants somebody to pull the lever to save him. But the party suggests that the trolley, in this case, will run over numerous victims of Saakashvili’s rule or, in a more catastrophic scenario, will roll with its passengers under the bombs of a mythologized second front which liberated Saakashvili would unleash alongside Russia (and with Western nudge).

President Zurabishvili, on the other hand, thinks the trolley has been running in a “closed circle” all this time, destroying everything and everyone on its tracks because the country cannot make up its mind on which way to divert it. Unlike the government, she does not believe that diverting the car from Saakashvili will cause much destruction. She hints that doing so may even help the trolley roll peacefully onwards, with all of the Georgians as passengers, into heavenly Europe. But Zurabishvili says she holds no lever, and the one she seemingly holds – her pardoning powers – can’t divert the trolley from crushing Saakashvili. She prefers to see herself as another passive passenger on that trolley. This might be so because President fears that her pardoning lever is, in fact, an emergency stop that might throw her under the wheels.

The United National Movement, Saakashvili’s party, sees no dilemma here. It claims the whole country is tied alongside Saakashvili, and the tram only has Georgian Dream members riding it. So diverting the trolley – even into an abyss – would solve all national problems. But the UNM has long failed to access the lever. Their dilemma is whether they will get the lever by tying themselves beside Saakashvili through parliament boycotts, rallies, or hunger strikes, hoping that the tram conductor would stop the car or pull the lever, or by tying the entire UNM party on the side track – offering existence in exchange for that of Saakashvili. None of these solutions seem to impress those with the actual lever or those in the cabin so far.

Most of the rest of the opposition has decided to get on the trolley like Zurabishvili and avoid looking at the track. In a state of powerlessness, they would rather see the tram rolling forward – discuss reforms in the parliament. Maybe they will pop a pill or two when it rolls over the body(ies?), shed a tear, but then would calm down and enjoy the ride alongside other passengers. Their resignation is understandable: each time they tried to join UNM in reclaiming the lever from the government, they ended up being gang-walked to the rails. They are told (and want to believe) that getting on that trolley with the GD would make the tram reach the final destination – the EU – faster. Unless, of course, bodies on the track derail them.

Some other opposition-minded leaders suggest building another trolley car from scratch on the parallel tracks or another sort of public transport altogether, hoping that the passengers would prefer to hop off from the doomed trolley… before or after it rolls over bodies.

Multitrack/drifting

Sometimes making a choice may be more painful than anything that comes after. To avoid this pain, trolley problem enthusiasts on social media (yes, we have reached into that niche) have offered a “multitrack/drifting” option, allowing a person to take both tracks simultaneously without having to choose one.

And that’s what Georgian foreign policy appears to be doing, at least based on the latest remarks and actions of our leaders. Government and ruling party officials have been comfortably repeating Kremlin narratives concerning the war in Ukraine while simultaneously posing proudly alongside U.S. and European leaders. Tbilisi, so far, seems comfortable in that mode. But in the end, multitrack/drifting can maximize pain and destruction, utilitarians would warn.

Take the ‘philosophical’ musings that pro-government media is actively circulating these days. “Is the European Union colonized and ruled by the U.S. worth this much worry?” government-and-conspiracy-friendly philosopher Zaza Shatirishvili asked this week. “Is the EU, where media is subject to full political control and censorship, worth this much worry?” he went on, enraging overwhelmingly pro-European Georgians.

Of course, philosophical problems require philosophical solutions. But this particular philosophical problem arose from, well, a very practical pecuniary problem. Ruling party founder Bidzina Ivanishvili is enmeshed in a battle with Credit Suisse over his assets. Since Ivanishvili is beside the trolley driver as a mentor, his solution is to throw the rest of us under the wheels and see if it helps him. But the problem is – billionaire’s lawyers complained this week – the western media won’t publish their sponsored articles. Hence they complain about “censorship” and “monopolization.”

We struggle to figure out how exactly this minor inconvenience over the assets of a privately suffering billionaire creates the philosophical abyss sufficient for questioning Georgia’s constitutionally declared foreign policy.

What we could find out, however, is why the country is experiencing problems with media freedom: our rulers have been confusing censorship with editorial independence.

And speaking of censorship >>>>

Art of self-theft

Can you steal yourself? Absolutely, if you live in a state that thinks it owns you.

This is what happened to Sandro Sulaberidze, a young artist who earlier this month staged a performance during one of the exhibitions in the national gallery: he removed his self-portrait from the wall and instead spraypainted “Art is alive and independent,” a phrase many saw as a protest against the current repressive drift of the Culture Ministry under its pharaonic manager, Tea Tsulukiani.

What happened next left little doubt concerning the validity of that drift: the national art museum promptly said that “the effects of damage to the National Gallery by the artist have been eradicated” (bureaucratic talk for “we painted over the spraypaint”) and also apparently happily reported the crime to police who have been investigating the artist on charges of… theft. He may get away with a fine or may land in jail.

This drew a huge backlash, including from fellow artists who went to repeat the graffiti near the Culture Ministry building, pointing to a difference between art and crime. The gallery manager tried to defend herself, saying she just followed the legal procedures (familiar excuse?) and assured the public that the artist only faced a fine, which had already been covered by exhibition sponsors.

She went on and called on artists “to plan performances without breaching the law” or be prepared for legal punishment.

The problem is that only a few in Georgia expect the punishments to be proportional and reasonable these days.

And the trolley rolls onwards…