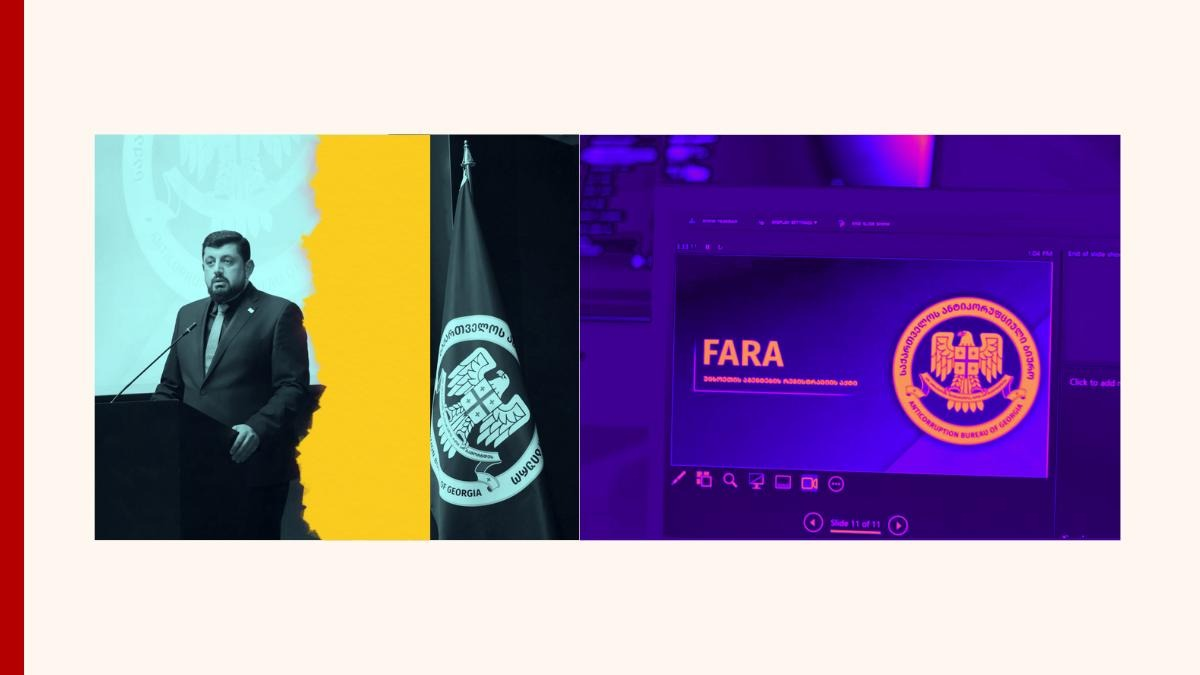

The Georgian interpretation of the American Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) took effect on May 31, amid widespread fears that the vague legislation would be used to further crack down on freedom of expression and association in the country.

The law is an exact translation of the U.S. FARA document enacted in 1938. It mandates that those considered “agents of a foreign principal” register within ten days in a special FARA registry administered by the Anti-Corruption Bureau. Those who defy will face harsh penalties, including criminal prosecution and jail time.

Due to the ambiguity of the text translated from the common law system without its interpretative precedents, and the hostile rhetoric of the Georgian Dream party that adopted it, observers expect it to be applied arbitrarily and selectively against the ruling party’s designated enemies. These are precisely the groups that the American legal practice largely exempts from FARA, such as independent media outlets, watchdog groups, or simply individuals critical of authorities.

“You have two options: you are either an agent or go to jail,” said Nino Zuriashvili, a Georgian investigative reporter, after leaving a meeting with Razhden Kuprashvili, the head of the Anti-Corruption Bureau. The week before the law took effect, Kuprashvili met representatives of various groups, including international organizations and local watchdogs, to clarify the minutiae of its application.

However, for some participants, the meetings left more questions than answers. “You should come and register after May 31, and then we will decide whether [FARA] applies to you,” Zuriashvili cited the agency representatives, pointing out that no clear definition has been provided as to who the Agency intends to classify as “foreign principal’s agent.”

Adopted this spring, FARA is the third “foreign agents law” introduced by the Georgian Dream parliament since 2023, and the second one that became the law. It will remain in force along with the Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence, passed by Georgian Dream last spring but yet to be strictly enforced.

Unlike the “Transparency” law, a.k.a. the Russian Law, which imposes heavy administrative fines on foreign-funded organizations that fail to register, the Georgian FARA also extends to individuals and provides for criminal liability for noncompliance. Penalties range from fines of up to GEL 10,000 (USD 3,650) to criminal charges and imprisonment of up to five years, or both. There is also a deportation clause for noncompliant foreign nationals.

The context is heavy with repressive policies. The FARA takes effect shortly after GD’s one-party parliament rubber-stamped additional legislation to shrink the space in which media and civil society can operate. This includes recent amendments to the Law on Grants that require foreign donors to seek approval from the executive branch before disbursing grants, and amendments to the Law on Broadcasting restricting funding for radio and TV channels and allowing the government to increase its control over the information they disseminate.

Anyone can be an “agent”

As with previous foreign agent laws, many groups and individuals have publicly vowed to defy it and not to register.

In Georgia, as in many post-Soviet countries, the term “agent” is often used as a derogatory term synonymous with a “spy” or traitor. This term has been extensively used in this precise meaning by the Georgian Dream officials and their media mouthpieces against the party’s critics. Last spring, Zuriashvili’s own outlet, Studia Monitori, was among the organizations whose offices were vandalized in a series of attacks that many believe were organized by Georgian Dream in response to protests against the reintroduction of a foreign agents law. “There is no place for agents in Georgia,” read posters the vandals left plastered on the walls, complete with Zuriashvili’s portrait.

While the scope of application of last year’s foreign agents law was relatively straightforward, the ambiguity of the provisions in the Georgian Dream’s FARA creates further confusion regarding who qualifies as an “agent.”

“There is no provision in this law that isn’t ambiguous,” Nika Simonishvili, the former head of the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, told the Mautskebeli podcast on May 30. The law “is a political instrument whose main thrill is to leave as much ambiguity and as many question marks as possible.”

The law copies verbatim the U.S. definition of the agent as “any person who acts as an agent, representative, employee, or servant, or otherwise acts at the order, request, or under the direction or control of a foreign principal” and engaged in Georgia “in political activities for or in the interests” of the foreign principal. The list of those who can qualify as “foreign principals” ranges from foreign governments, organizations, and companies to foreign individuals or even Georgian citizens who are not permanently residing in Georgia. Per law, the burden of proof on whether one qualifies as a “foreign principal’s agent” falls on courts, which have served as pliant instruments of political justice in recent months.

The interpretations reportedly provided by Anti-Corruption Bureau’s representatives during informational meetings paint a different, even grimmer picture.

“If you have shared a public post critical of someone or went to a protest demonstration … all this qualifies as political activity,” said Nino Zuriashvili after the meeting. According to Zuriashvili, she was told in the meeting that one still qualifies as an agent if the foreign source of income is not directly related to the “political” activities one might engage in while exercising one’s rights as a citizen.

Accounts from the meetings and the absence of independent institutions that are supposed to prevent the arbitrary application of the law led some to speculate about absurd scenarios: for example, one might qualify as an agent simply for writing a critical social media post while receiving financial support from a family member who permanently lives abroad. Many Georgian families depend on such remittances.

With this interpretation, the Georgian Dream authorities “are putting a significant portion of the Georgian population at risk of criminal persecution,” Simonishvili said. The lawyer described the application of the FARA in the Georgian context as a “complete legal nightmare.”

Tough Choices

Those targeted by the Georgian Dream’s FARA will now face tough choices about what to do next.

“Under the broadest, even if false interpretation of Georgian FARA, any person with a contract with a foreigner (or a Georgian national residing abroad) as of May 31 may be required to register as an agent,” Saba Brachveli, a lawyer with the Georgian watchdog group Civil Society Foundation, wrote in a Facebook post on May 27. Brachveli argued that the American judiciary and Justice Department have narrowed the scope of FARA’s application in the U.S., but these interpretations were disregarded when translating FARA into the Georgian context.

The lawyer says this leaves representatives of Georgian organizations, media outlets (except broadcasters), and companies with three options: 1) stop operating, 2) register on a portal that is seen as humiliating and deal with bureaucratic procedures, including labeling oneself as an “agent” in public communications, or 3) continue functioning without registering and try to resort to available legal mechanisms, including request the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) to pass an interim measure and stop the law’s application.

The Anti-Corruption Bureau has launched a FARA website resembling a similar website in the U.S. The website features a “FARA e-file” portal for submitting registration applications and related documents online.

It also displays contact information and encourages citizens to report individuals/organizations who they believe are “breaching any norm of the law or have an obligation to register and are not registering.” The note fueled dark comparisons to the 1930s, when similar reporting practices underpinned the Stalinist purges in Soviet Georgia.

It is unclear how strictly the law will be enforced. But the introduction has already had its chilling effect. Civil.ge has received reports of staff members, not necessarily in executive positions, quitting their longtime jobs at foreign-funded NGOs due to concerns about the harsh punishments that the GD’s FARA foresees. It remains unclear whether individual staffers in organizations that refuse to register may also be persecuted.

However, the Georgian Dream authorities have already backpedaled on applying the law to staff at diplomatic missions and international organizations (IOs) in Georgia. While accredited diplomats and IO staff are exempt from Georgian FARA by default, missions were initially asked to submit lists of non-accredited staff to the Anti-Corruption Agency for processing additional exemptions. However, a document seen by Civil.ge reveals that the GD Foreign Ministry officially confirmed to diplomatic missions and IOs that non-accredited staff “are, by default, exempt from both the registration requirement under the FARA and the obligation to submit exemption forms.”

“Even the Anti-Corruption Bureau is unaware at this point of how (or whether) the law will be enforced,” says Brachveli. “But if they proceed down this path, [the application] will likely be selective.”