Dispatch – June 24: The Newspaper

We all wanted to start “a newspaper.”

For many years, newsstands across Georgia offered a poor selection. There were one or two moderate newspapers that somehow survived the national aversion to the print press. But their spotlight was long lost to more sensationalist headlines from a slowly growing variety of conservative, conspiratorial publications. These were so bored with the absence of rivalry that their editors waged wars among each other over how to translate “deep state” into Georgian correctly: finding the right words for this new, all-explaining phenomenon was an urgent matter. There was an even bigger selection of crossword newspapers, in Georgian or Russian. There were also a couple of Russian women’s magazines, a solitary issue of National Geographic, and a series of fancy-looking editions of Forbes, Burda, and Entrepreneur.

“That one newspaper”, however, was missing: the talk of the town, something that liberals would buy but would also attract a broader range of readers, something we’d all be discussing or fighting about the next day. The trouble was that we didn’t (want to) believe readers still existed. Nobody reads these days, we’d tell ourselves, everyone’s into podcasts now, and social media favors reels. At least nobody will pay for a paper – that’s not how poor Georgia works.

But then the next day, we’d feel this renewed, inexplicable urge to start a “newspaper.” It became our liberal savior complex: a newspaper with the right facts and views that you’d distribute among senior citizens “in the regions,” to the men playing backgammon and wearing flat caps, to the women sitting on the porches during short breaks from their invisible round-the-clock labor, with faces tired and heads covered. The images of good but naive citizens, curiously leafing through big papers and immediately cured of the propaganda disease, lived rent-free in our minds.

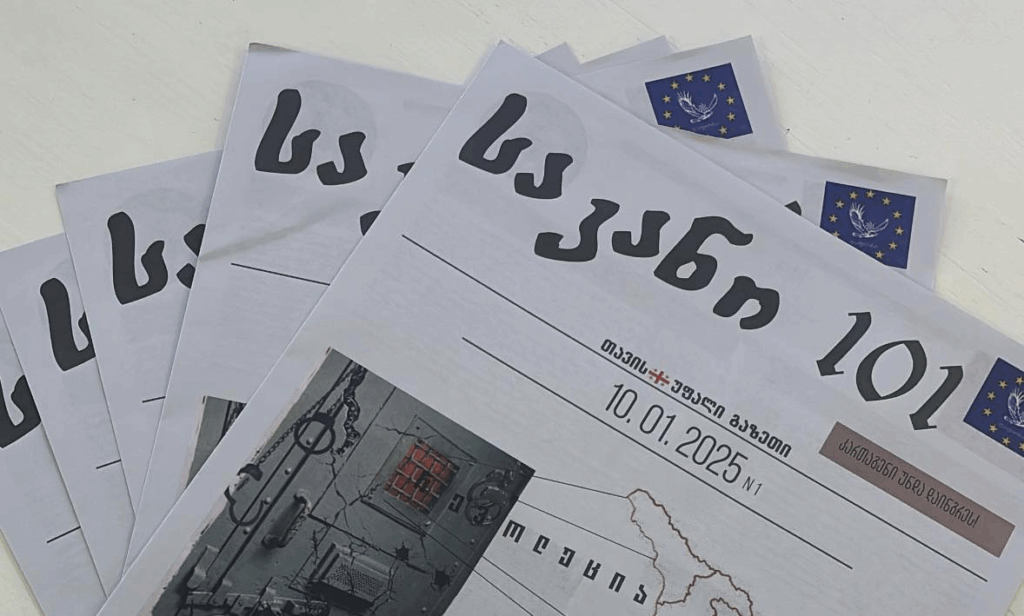

There were one or two attempts to actually print things out. They went nowhere, perhaps because they were half-attempts and more resembled brochures than the products of an ambitious media project. The publication of those real “good newspapers” was delayed indefinitely. The newspaper that would reform us, that would humanize us all, was left pending forever. It was delayed so long that, by the time those newspapers were finally printed, all of them were either about political prisoners – or by political prisoners.

Here is Nini and the Dispatch newsletter with a weekly editorial column about what bothers Georgia.

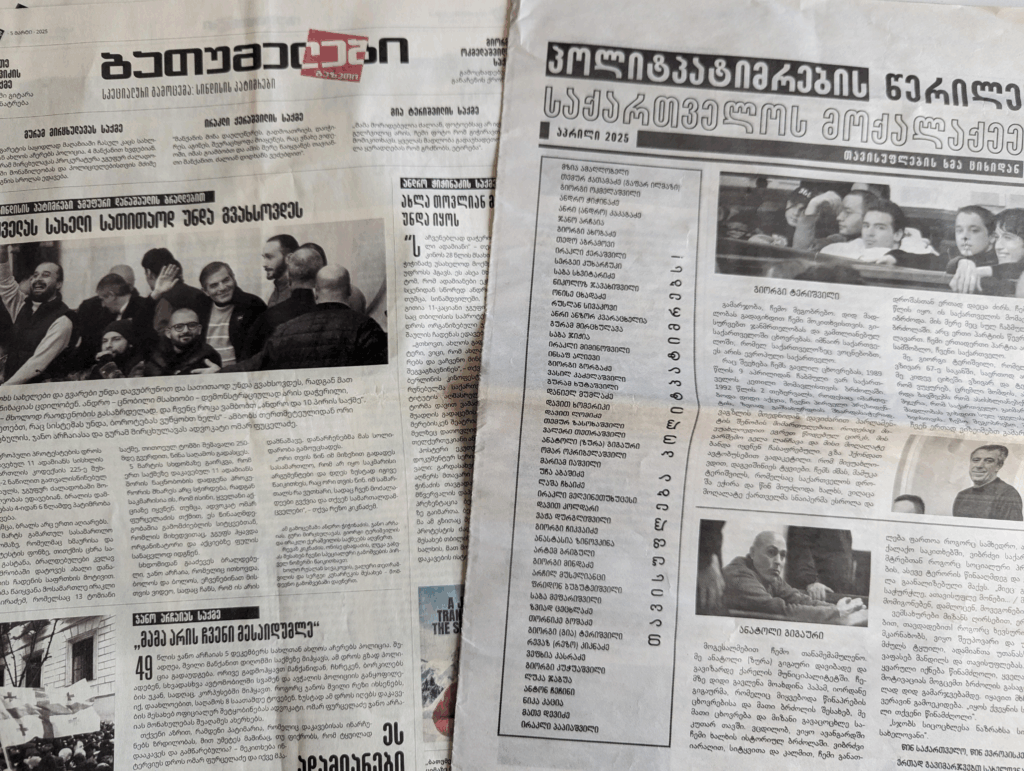

The newspaper has now been everywhere. It first appeared at daily rallies on Rustaveli Avenue, distributed in front of Parliament. There was Cell 101, a paper published by Zviad Tsetskhladze — the activist and law student detained on group violence charges, who turned 20 behind bars. Batumelebi, a popular media outlet that has covered the coastal Adjara region since 2001, also returned to its original print form after its founder, Mzia Amaghlobeli, was imprisoned.

Then came another special issue — Letters of Political Prisoners to the Citizens of Georgia — which gradually made its way beyond downtown Tbilisi, reaching distant neighborhoods of the capital and towns across eastern and western Georgia. A group of activists, including family members of detained protesters, delivered the papers by hand, bringing to life the scenes that those newspaper dreamers once imagined.

The articles are good to read. Those in Batumelebi special issues, for example, provide summaries of political prisoners’ cases, combining details of the charges and context with more intimate glimpses into the lives of inmates before they ended up behind bars. These well-crafted features, co-written by Amaghlobeli’s colleagues from different outlets, help fill the widening gaps left by an increasingly strained online media, which found less time for storytelling artistry while caught in a constant cycle of reacting to news, events, disinformation, and growing attacks on the press.

The papers are here to fight many wars, but their main battle is against statistics. “We need to return the names and surnames to these people, because they try to dehumanize them,” a lawyer is quoted on the front page of one of the Batumelebi special issues, under the courtroom photo of what’s become known “Eleven Prisoners of Conscience,” one group of protesters detained over group violence charges.

The names are easy to forget. Nearly seven months into non-stop resistance, each week has felt worse than the last. Every week, something happens for the first time: a protester arrested, a journalist jailed, a politician detained, a woman imprisoned, an activist locked up for “insult,” a critic fined over a Facebook post, someone’s home raided, an NGO inspected, a protester convicted, a repressive law introduced, another repressive law adopted, a politician sentenced, another politician sentenced, three politicians convicted, four… First comes an event, then it becomes a trend, and before you know it, it can be reduced to just a number.

In Another Life

“None of this would be happening if we’d started that newspaper,” we sometimes joke in Civil.ge office. We, too, once had that newspaper dream. We even started writing and planning, but we never believed enough or tried hard enough. But is the none-of-it part truly a joke?

Newspapers aren’t the only projects that everyone thought were needed, but that only became possible in darker times. As the protests dragged on, things we once thought were impossible suddenly became possible. People learned to crowdfund as key civil society initiatives were stripped of vital funds. A stable progressive political project emerged from daily rallies, after many years of everyone arguing it was impossible despite a clear need: there were not many leftists around, those that were around were busy fighting each other, and even if they had united, with so little funds they’d never stand a chance against big money.

But desperate times also mean greater hurdles. The newspaper boom has yet to spark a true reading culture or a commercially viable, reader-funded model. The progressive project — the Movement for Social Democracy — is still far from becoming a fully functioning political party, and the current repressive climate suggests the authorities may not allow it. And while crowdfunding efforts are everywhere, anyone thinking of launching something long-term, hoping to survive on citizen donations, still has to think twice, especially when so many who would gladly help have already lost their incomes.

Another reason we are not there yet is that Georgians are still figuring out where they are exactly with the protests. Is this a long-term battle, where resistance becomes life? Or are they simply waiting for the right moment, for that implosion, that awakening after which everything returns to “normal” in a matter of days? The shock and confusion leave many in a state of ever-deepening reactive numbness, making it harder to mobilize, organize, or take initiative.

And still, would any of this be happening if we had all committed to those dream newspaper projects? We’ll never know. But if someone, somewhere, is contemplating a project they believe is vital for a better society, for better politics, but thinks they can’t afford it, trust us: you can afford it.

You’re just not desperate enough. Yet.