Dispatch – February 26: Broken Embrace

It is late February, which means that hardly a day goes by in Georgia without us commemorating some historical event – mostly tragic, sometimes joyful, but always in some unfortunate context. Why February? Perhaps this is a time when the bear comes out of hibernation, and thus Russia’s neighbors suffer. On February 24, Georgians sent their thoughts and prayers to those killed as a result of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine two years ago. The next day, February 25, marked one of the most tragic dates in Georgian history – the day Tbilisi fell to Soviet Russia’s occupation in 1921.

Indeed, most of these sad anniversaries come from Georgia’s First Republic and its struggle for survival. The republic existed only for three incomplete years (1918-1921), a timespan eleven times shorter than its current, reborn version. Yet it left a lasting legacy that Georgia is still trying to fully appreciate – and to come to terms with.

Here is Nini and the Dispatch newsletter to look back in time and search for elusive links between the two versions of Georgia.

The First Republic is perhaps Georgia’s biggest “what could have been” story.

More than a century has passed since its brief existence, but its history never ceases to amaze, and its memory only becomes clearer with time. The republic emerged from the debris of the Russian Empire, out of the chaos of the post-World War I, in 1918. It lasted only three years before succumbing to Soviet occupation. Yet the political elites of that time achieved no less than its successor would do in 33 years. Georgia became the first European country to be ruled by social democrats; it implemented ambitious social reforms; it based its policies on compromises between classes, nationalities, and opposing political groups despite its ideologically driven leadership; it made foreign friends and attracted international attention. The list goes on.

The isolated young country has certainly had its economic struggles and political controversies, but against this backdrop, its achievements seem even more remarkable. Especially as all of this was done while fighting territorial wars with neighbors and living in constant fear of the Whites, the Reds, or the Ottomans/Kemalists.

The Soviets did arrive – twice, in fact. Georgia repelled the Russians in 1920 and concluded a treaty of mutual recognition of borders with the Kremlin. But then, as now, the word of the Kremlin rulers was not worth the paper it is written on. The onslaught took off once the Bolsheviks felt respite from the Western pressure in early 1921. The Georgian army bravely resisted the Red Army’s advance for six weeks. But ultimately, it didn’t stand a chance in an unequal battle and without the support of its Western allies, who lost interest in the South Caucasus once Baku’s oil fields were firmly in Russian hands. Some of the officials had to flee to form a government in exile; others stayed to continue the underground struggle but eventually fell to Bolshevik repression.

But one can also say that by the time darkness fell, the primary mission of the First Republic had been accomplished: the contours of the modern state were drawn, and the first progressive Constitution was passed. Georgia began a long wait to regain its independence, a moment that took seven decades to arrive. In 1991, Georgia seceded from the Soviet Union and restored its statehood based on the 1918 Declaration of Independence. But something was different this time.

Our Roman Empire?

The memory of the First Republic reached its successor in a distorted way. Long-standing Soviet efforts to vilify the 1918-1921 leadership merged with the fiercely patriotic sentiments of the new independence movement, turning the legacy of the “fleeing government” and its socialist leanings into something not to be proud of. Slowly, however, a growing number of scholars began to delve deeper into history and share more accurate findings with the broader public. The unique social-democratic “experiment” also attracted international academic attention. More and more Georgians began to take pride in its achievements and lament the Soviet Union for prematurely thwarting the dream.

To some, all that excitement may now look pathetic. Why so much obsession with “3 years of history”?! Wasn’t the Soviet “break” between them twice as long as the lifespan of both republics combined? Compare the press, politics, and discussions between the two eras, and it’s hard to imagine that they have anything in common beyond geography.

Except that sometimes the differences make more sense than the similarities.

The 3-year culmination

The three years of history are actually three years of culmination. The elites of the First Republic began laying the foundations as early as the 19th century amid the turbulent intellectual and political life of the Russian Empire. Various groups emerged to engage in political discussion, develop the press, and disseminate knowledge to the public. But while Georgia has largely retained the memory of prominent liberal-nationalist voices, the no less remarkable stories of more internationalist-minded social democrats – who would eventually lead Georgia into its first independence – are often obscured.

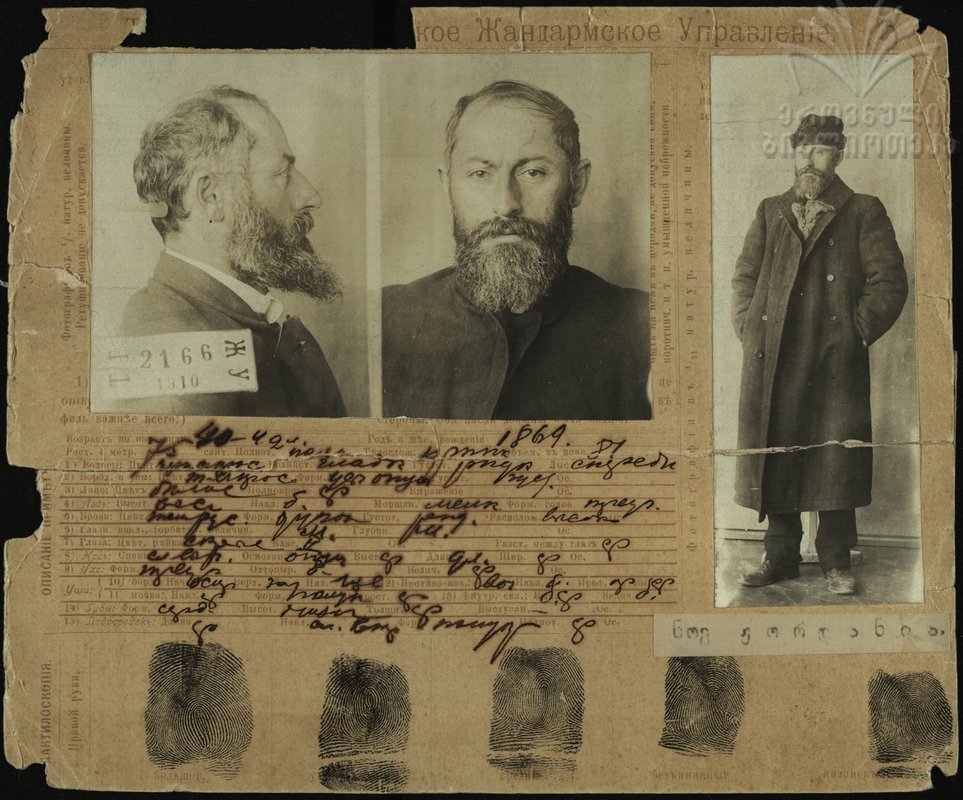

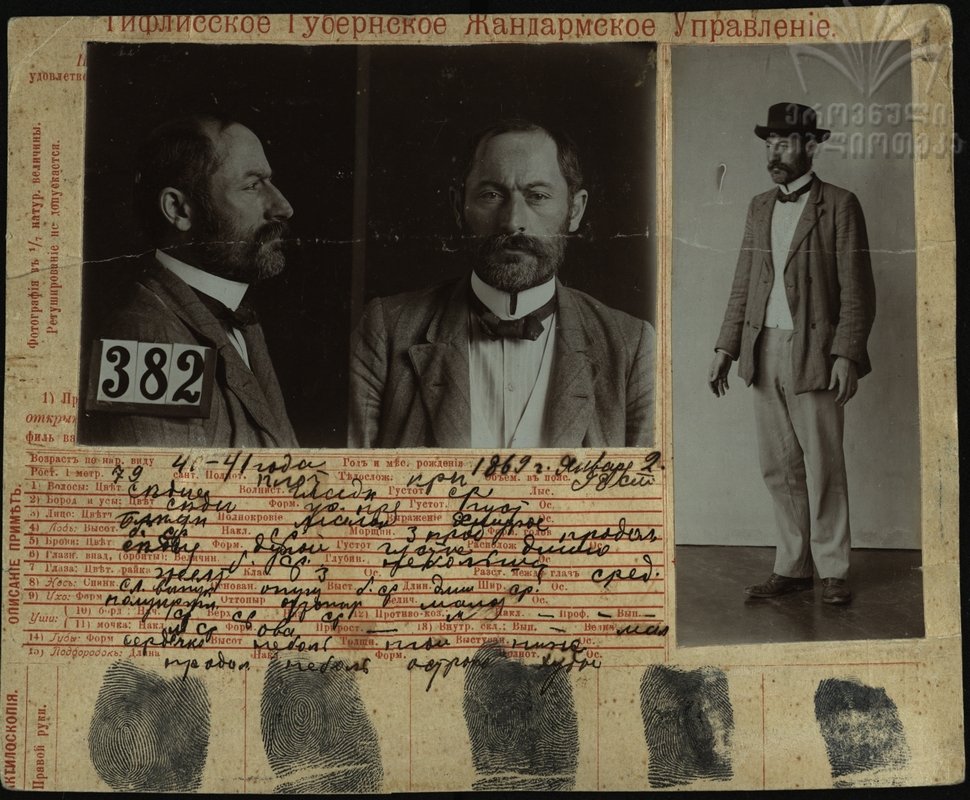

The stories of these leaders, such as government chairman Noe Zhordania, are filled with thrilling adventures of resistance and underground struggle, efforts to unite diverse brilliant (and incredibly well-dressed!) people around a common idea while traveling and forming friendships with prominent foreign colleagues. The Georgian revolutionary movement developed gradually, also rallying rebellious peasants as Georgia had a small working class. After the 1905 Russian Revolution, many of these Georgian Marxists – later Menscheviks – were elected to and dominated the moderate socialist factions in the Duma. Ideas were discussed and programs agreed upon everywhere, from local prison cells to distant European cities, from small-town meetings to imperial centers.

- Illegal revolutionary activities made Noe Zhordania, who, according to the Social-Democrat icon, Karl Kautsky, “united the talents of the practical fighter with the activities of the thinker and publicist”, a frequent visitor of imperial jails – and allow us to also trace his sartorial progress. Photos: National Library of Georgia

After the Russian (February) Revolution of 1917, in which Georgian Mensheviks played their part, the group returned to the Caucasus to work on various alternative political projects. At that time, not all of them had national borders in mind. However, strong nationalist winds of the time were also blowing toward Tbilisi, mixing with the dominant progressive ideas. In 1918, this mixture gave birth to the Republic of Georgia, where all the knowledge and ideas brewing among these groups would find their best outlet. The elites embarked on the short-lived but ambitious and fruitful path of nation-building despite the ever-present threat of renewed Russian occupation – a mentality with which the successor republic would struggle mightily.

3 vs 33

Unlike the original version, today’s Republic of Georgia was born from years of national liberation struggle. During that dramatic battle, in which flags were waved, and blood was spilled, leaders may have forgotten that building a state takes more than flag-waving and spiritual soul-searching. That’s hardly surprising: years of totalitarian Soviet rule had erased memories and left little room for political deliberation. The clearest memory Georgia carried into its second life was one of loss – build what you want, but someone mightier than you will come and take it away.

This memory, the subsequent wars, and the lingering foreign threat have taken their toll on the political culture: in politics, as in many other areas, Georgians often behave like death-obsessed teenagers who have just become aware of their own mortality and don’t know what to do with that knowledge: live as if there was no tomorrow? Not live at all? And so today’s politics resembles a clash between two extremes – those of inaction versus recklessness. The Russian invasion of Ukraine two years ago may have only intensified the subconscious fears (for some – even perverse hopes) of impending doom. The country has yet to learn how to make ambitious, visionary politics and simply how to project itself into the future.

At the moment, Georgians are still figuring out what to do with the rehabilitated memory of the First Republic. Obsess with it? Glorify it? Mourn it? Use it for self-victimization? Turn it into bedtime stories for the grandchildren? Or maybe it’s time to inherit one of the most important characteristics of the past and its politics, which is a constant preoccupation with the future.