Will you fight or will you flee if things get really bad?

The question has long haunted Georgians who haven’t seen much peace or stability. The insecurity was easy to forget when going through the daily hustle or while relaxing afterwards. But then, whenever Russia invaded our friends, or the Middle East exploded, or tensions flared in the South Caucasus, scary thoughts crept back in. Some were determined to fight, even with their bare hands. Others would say they’d buy a one-way ticket and board the first plane, arguing their sacrifice wasn’t worth it.

The thing was that “things getting really bad” always meant bombs and fire and noise and action. But we’ve lived long enough to see that things can get really bad rather slowly and peacefully. Little seemed to have prepared us for that, or for the fact that for many a country’s citizens, the response to a threat would not be the proverbial fight or flight, but rather “freeze”- or playing dead. The writings of a jailed poet, however, suggest that it’s not the lack of experience that made part of Georgians so ill-prepared, but the opposite: a rich history of playing dead before.

Here is Nini and the Dispatch newsletter, back with a regular editorial column telling the story of Georgia.

Hate the repression if you must, but it may appreciate creative expression more than some of its targets do. Repression first triggered a newspaper boom in Georgia. Then, when courts closed doors to cameras, it pushed artists to produce memorable courtroom sketches while forcing writing journalists to explore long-forgotten narrative genres. Repression was also how earlier works of Zviad Ratiani, a Georgian poet and translator, found their new readers.

Ratiani, 54, was arrested late on the evening of June 23 over slapping a police officer during the Rustaveli Avenue rally. Little is known about what triggered the confrontation, but those aware of court practices have little hope that the poet will leave the cell anytime soon. The arrest led Georgian protesters to reread Ratiani’s long, clearly worded, and unconventionally rhythmic verses, only to find that they offered a scarily accurate depiction of Georgia’s current state.

“We, who will never come outside,

Nor join our voices with the hungry knights,

Or sign our surnames to the protest lines,

And if others trust us, we will pull them, too,

Away from such deeds, the great deeds…“

– read the first lines of Negative. 20 Years Later – Ratiani’s one of the best-known poems. Then it goes on:

“We, who’ve never stood waiting at locked doors,

And if we enter, only where we’re allowed;

Who shut our windows, and draw the curtains low,

When desperate cries for help reach from outside.”

The lines go on and on, with further “we-s” and more “who-s” – about those who refuse to trust not only their ears, but their own eyes, too, and those who try not to stand out – neither by weakness, nor by courage, and those who turn down volume when hearing local news only to turn the TV up at full blast for international coverage “where there’s nothing more to lose or, rather, to hide”.

The lines ring too true whenever Georgian protesters feel let down in their ongoing battle. But the poem was composed back in 2008 and from there, too, the lines travel further back in time, two decades earlier, tracing the roots of the resignation and finding them in the years of upheaval, when the patriotic excitement of the 1990s quickly turned to ashes through conflicts and unrest. “Son, we weren’t always like that”, the poem goes, “you must have seen these eyes twenty years ago.” The poem then returns to the present-day apathy, having answered the questions on why “we’ll never again come outside” and “won’t be leaving our mark anywhere but in dreams.”

Negative. 37 Years Later.

Nearly two more decades passed since the poem was published. One government was ousted through elections, largely due to its poor human rights record, and it took some time for the new one to develop a repressive urge. When that happened, Ratiani was among the first victims.

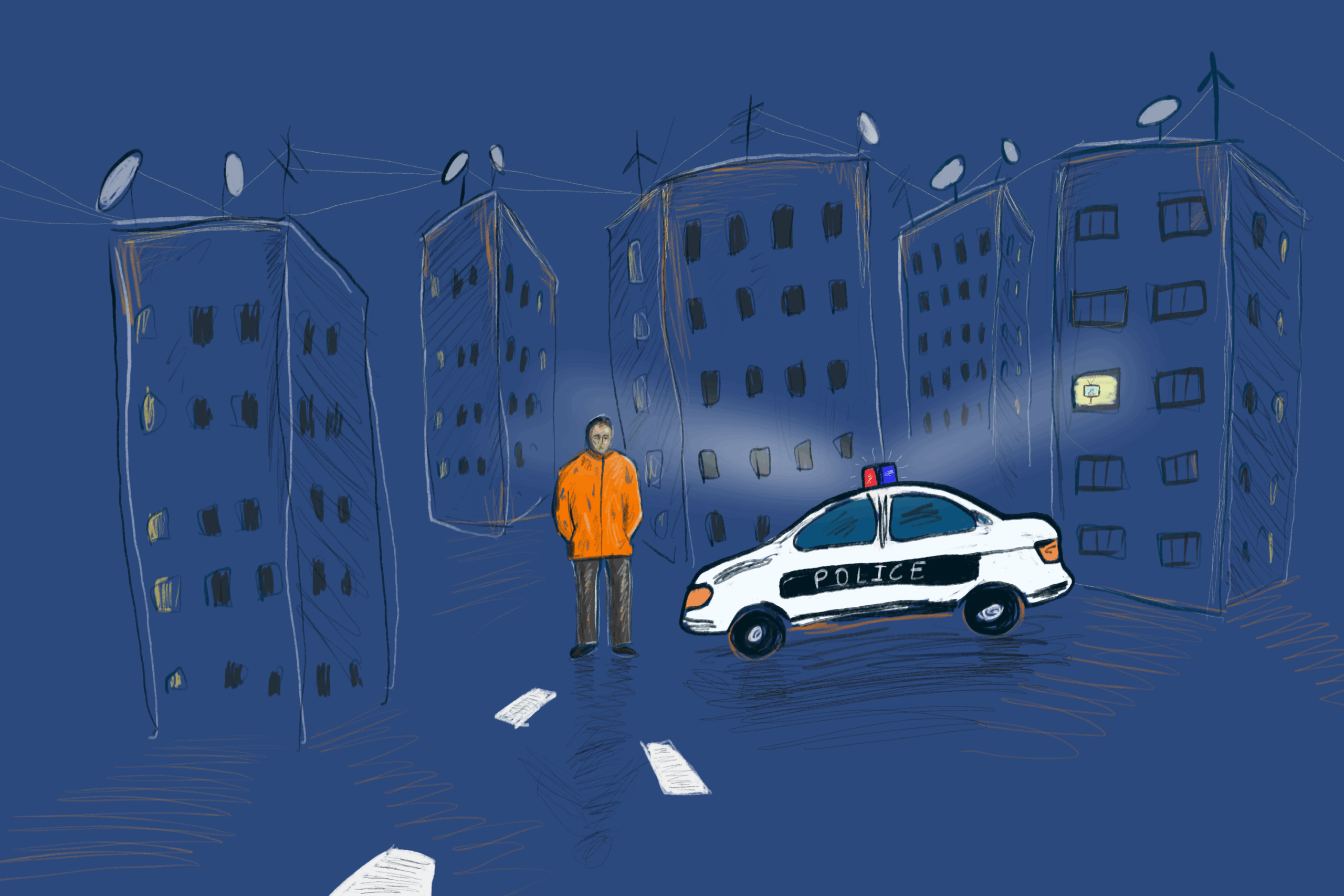

In the winter of 2017, Ratiani was subjected to— in the words of Salome Asatiani, a Georgian intellectual— a Kafkaesque treatment after a police raid found him during a lone night walk. The unhappy encounter culminated in an alleged beating, and Ratiani would recall that police singled him out for his apparently insufficiently conservative orange jacket. When his colleagues raised alarm over the mistreatment, authorities went on to add insult to injury, circulating a video showing the author in distress— lying on the ground, or later sitting in sullied clothes with his hands tied by police— swearing, yelling, and cursing at the Georgian Orthodox Church Patriarch, among others. All the while, police officers are heard gaslighting him with repetitive “calm down, citizen” phrases.

The desperate condition of Ratiani, allegedly triggered by the abuse he endured, was powerless to win him public sympathy: his verbal condemnation of the Patriarch, Georgia’s most venerated man, was a crime enough to overshadow the mistreatment. The sense of defenselessness from propaganda machine and backlash soon led the poet to seek refuge in Europe.

Years later, Ratiani found the strength to return to his homeland, only to find Georgia in the grip of a fresh wave of repression, where he, again, was among the first victims. Ratiani was detained on November 29, 2024, a day after non-stop protests erupted in response to Georgian Dream’s announcement to halt EU accession. He spent eight days in jail and later recounted being subjected to beatings and insults at the hands of police.

After the detention, the author became one of the loyal Rustaveli Avenue protesters who stood their ground as apathy set in and the crowds in the street slowly dwindled. Those months felt like an evil reenactment of his poem’s plot: the excitement of the initial weeks of protest, which at times felt like celebration, quickly descended into exhaustion and depression. What remained were the cries of disappointment from a dwindling few, directed at those whom they saw retreating from the fight.

Fight, Flight, Freeze

It seemed that the shock and pace of the rapid descent into authoritarianism sent many into a kind of denial, a frozen hibernation that allowed them to dissociate from the events and their civic responsibility. This was not happening, or not happening to them. That frost affected both erstwhile liberal fighters and Georgian Dream supporters who, while voting for the ruling party and despising the opposition, had never truly signed up for mass political jailings or the loss of Georgia’s key achievements with the EU.

Things kept happening in those months that were supposed to revive the fighting spirit. We saw our neighboring countries resisting Moscow’s influence and getting away with it. We saw young men sentenced to years in jail, and we were never meant to tolerate it. We saw Georgian Dream caught in internal purges and scandals, undeniable signs that something was shaking inside the party, and it was time to act. We were losing EU benefits while fellow applicants were only gaining more. And yet, somehow, the very things that were supposed to trigger a fight response ended up freezing us up even more.

There must be a scientific explanation for it. Is our instinctive stress response ever truly a choice? Are we born with those instincts, or do they stem from early, unexamined trauma? Are we asking too much of too many, or is this simply what comes out of a dysfunctional society?

It may take time before we uncover the cause, or the cure, for this collective freeze. For now, the only accessible remedy seems to lie in the determination of those who could neither flee the terror nor play dead, even if they tried, the ones who found no other choice but to keep fighting. The jailed author was among them.

We Who Will Always Come Outside

“Fleeing has become an integral part of his poetry over the years,” literary critic and editor Malkhaz Kharbedia wrote in a 2010 blog post for RFE/RL’s Georgian Service, reviewing Ratiani’s poetry collection Negative. The blog quotes Ratiani himself, as noting that most striking about his earlier four collections was “an attempt to escape, or rather, unsuccessful attempts.”

Kharbedia, editor of literary magazine Arili, who tragically passed away only weeks before Ratiani’s latest arrest, then observed that instead of imagining the future, Ratiani “is putting the past in order, he’s trying to see it.” In one of the poems, as the critic notes, Ratiani even thanks God above for endowing him with rich “talent for seeing the past” while denying him any gift of foresight.

A decade and a half after that observation, we’d find out that there is no better way to see the future in Georgia than to look into the past, and simply “put it in order.” Yet as much as the poet’s supporters admire his prophetic talent, they refuse to accept the prophecy itself. Instead, some have chosen to gently revise the opening line of his most famous work, and make the new version their guiding principle:

“We, who will always come outside.”

***

Note: the poetry translations in this column are amateur and in no way do justice to the original.

Another Note: Dispatch is a free newsletter, and we are determined to keep it free. But for that, Civil.ge needs to survive. You can support us by subscribing to our premium daily newsletter or by donating here.